The Elder Abuse Policy Landscape in the US

Heidi Gullett, MD, MPH

Charles Kent Smith, MD

Patricia Hughes Moore, MD

Case Western University

Charles Kent Smith, MD

Patricia Hughes Moore, MD

Case Western University

|

Download article:

|

| ||

ABSTRACT

This paper presents lessons on the equity of healthcare and health for older people that emerged from the experience of a COVID-19 incident commander during the pandemic. The lessons include the value of ongoing investment in trustworthy cross-sector relationships and value-added roles for learners; the importance of working together for the common good which can provide a deep well to draw upon during a crisis; in such times, the vulnerable often become more vulnerable and need extra attention thus meeting the needs of older people requires consideration of age, disability, and congregate living status; an equity lens and cultural humility foster new opportunities for community health and systems thinking, and when balanced with on-the-ground work and relationships, make it possible to take on seemingly intractable problems; in order to advance community health and equity, it is vital to meet both immediate needs and to focus on strategic efforts to simultaneously transform systems and structures; developing new knowledge creates opportunities for broader sharing; interprofessional teams enable collective action in a complex problem; transparency and continuous communication are important always, but vital in a crisis; and proactive investment in public health infrastructure could mitigate a future crisis. While the pandemic produced loss and pain for millions, the transportable lessons about investing in system science, equity-focused, cross-sector infrastructure, and relationships can inform the future of public health and health care policy, grounded in lived experience, to inform the re-emergence of collective efforts to foster health equity for older people and other vulnerable populations.

Keywords: pandemic, systems thinking, congregate living, community health

Drawn into the Local Eddies of an International Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted life in profound ways across the lifespan, but has been especially brutal for historically marginalized populations (Laurencin & McClinton, 2020; Lin, 2020), those living in congregate settings (Terebuh et al., 2020), and particularly for older adults (Banerjee et al., 2020; Gorgulu & Duyan, 2020; Shahid et al., 2020; Tisminetzky et al., 2020; Wynants et al., 2020). The following insights are the result of lessons learned on the ground in first year of the local Cuyahoga County Board of Health (CCBH) COVID-19 response, with particular emphasis on the pandemic’s outsized impact on older adults, those with disabilities, and those living in long-term care facilities, as well as those from groups disadvantaged by race, ethnicity, and related socioeconomic inequities.

In Ohio by March 2021, more than half of the COVID-19 deaths occurred among those over 80 and 38% of deaths occurred in long-term care facilities (Ohio Department of Health COVID-19 Mortality Data, 2021).

Cuyahoga County, situated in northeastern Ohio on Lake Erie, is home to 1.2 million people in the greater Cleveland area. It was the site of the state’s first COVID-19 cases as the pandemic arrived in the Midwest (Bureau, 2019; Cuyahoga County Board of Health, 2020), and The Cuyahoga County Board of Health (CCBH) is the largest local health jurisdiction in the state of Ohio, and serves 58 of the 59 municipalities in the County. The city of Cleveland maintains its own health department, but works in close partnership with the CCBH.

I served as the CCBH Incident Commander at the start of the pandemic. An Incident Command structure organizes cooperation among multiple agencies within and outside of an organization (in this case governmental public health) to coordinate response to a crisis. The Incident Commander establishes communication channels, brings together diverse sectors and individuals, organizes training, and establishes structures and processes needed to respond to an incident―such as a global pandemic.

Emergent Lessons Learned

Ongoing investment in trustworthy cross-sector relationships and value-added roles for learners working together for the common good, can provide a deep well to draw upon during a crisis.

In taking on the Incident Commander Role, I largely set aside, but drew frequently on, my regular job as a family physician at a busy community health center, and as a medical school faculty member teaching and conducting research. For this role I had some background as a physician trained in family medicine, public health and preventive medicine. However, even more important than my formal residency training, was seven years of investment by myself and my university (Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine - CWRU) in placing me as the population health liaison in the local health department. In that role, I got to know people within and outside of public health and health care who would be vital to a coordinated response. I had come to know both the powerful and the vulnerable by serving as co-leader of our county’s community health improvement plan and had developed relationships that emerged as the mortar that held together the building blocks for crafting a new infrastructure that did not exist for a crisis of this magnitude.

Working with the County Health Commissioner, we began to prepare shortly after the first US COVID-19 case was reported outside of Seattle on January 20, 2020. This preparation involved meeting for several weeks with local and state partners. In collaboration with our state partners, we then reported the first Ohio cases in our jurisdiction on March 9, 2020. The days and weeks that followed involved rapidly and simultaneously assembling a COVID-19 response team, along with using the incident command structure internally to realign our staff and externally to engage partners to meet the needs of our community. The entire COVID-19 response also had to occur within the context of ensuring that the CCBH continued to meet the ten essential functions of public health[*] for all conditions affecting the community, in addition to COVID-19 (10 Essential Public Health Services, Updated 2020).

The CCBH COVID-19 response team included long-time public health professionals with expertise in epidemiologic and infectious disease investigation, data management and analysis, environmental inspections and control mechanisms, and communications, as well as learners across the medical education continuum from medical and physician assistant students to resident physicians. From the first week of cases, the team met twice daily in tactics meeting to review rapidly changing data and community needs, further refine ever-changing workflows, identify infrastructure and communication needs, and to encourage one another through regular sharing of gratitude and self-care. The latter became increasingly important as cases and community needs grew exponentially along with challenges in supply chain, testing availability and understanding of behavior of the novel virus at the center of the pandemic.

Case Study: Trusted Relationships and Value-Added Roles for Learners

At the beginning of the pandemic, rotations in traditional clinical sites were limited for safety reasons for medical students and resident physicians. Due to the longstanding relationship between CCBH and the CWRU School of Medicine, including seven years of investment in the role of embedded population health liaison, we were able to rapidly design and deploy a medical and physician assistant student elective that enabled learners to obtain school credit for a telemedicine rotation, while being trained in public health case interviewing and contact tracing. Beginning just over a week after our first cases, medical students joined the COVID-19 response team as case investigators and contact tracers. In total, 80 first through fourth year medical and physician assistant students from CWRU School of Medicine contributed over 5000 hours to the COVID-19 response between March and June 2020. These students conducted telephone interviews with a rapidly growing number of cases, participated in contact tracing, performed discontinuation of isolation interviews, coordinated resource needs, communicated with facilities experiencing outbreaks and contributed to quality improvement cycles on workflow improvements (Gullett, 2021).

The long-standing CCBH commitment to teaching and investment in public health workforce training, which includes formal agreements with nursing and medical schools that predate the pandemic, created almost instant capacity in the rapidly evolving pandemic.

Beyond the impact of undergraduate medical education students, Public Health/General Preventive Medicine resident physicians (PMRs) and faculty members from CWRU and University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center were pivotal in the early response and formed a COVID-19 physician response team. PMRs normally rotate at CCBH as their primary location for local public health training throughout residency, thus they were already credentialed and able to begin working at a high level in providing clinical guidance on cases and contacts, analyzing data, taking responsibility for managing community and congregate living facility clusters, developing workflows and guiding the evolution of response infrastructure within the COVID-19 incident command structure.

In a crisis, the vulnerable often become more vulnerable and need extra attention.

To meet the needs of vulnerable populations, it was important to consider age, disability and congregate living status. Early on, congregate location trends showed high case counts and substantial loss of life due to COVID-19 across Ohio’s long-term care facilities which mirrored national trends.(Bernabeu-Wittel et al., 2021) Across the state from April 15, 2020, (prior data are not available at the state level) through March 31, 2021, the Ohio Department of Health reported 48,909 resident cases and 34,893 cases among staff in long-term care facilities (which include nursing homes, assisted living sites and intermediate care facilities) (Health, 2021). In Ohio, the median age of fatalities from COVID-19 is 80 among 18,609 deaths (Health, 2021). Among Ohioans who have died from COVID-19, 14% were aged 60-69, 27% aged 70-79 and 52% were aged 80+ (Health, 2021). Furthermore, greater than 38% of all Ohio COVID-19 fatalities (7,119 of 18,609 between 4/15/20-3/31/21) occurred in long-term care facilities within four of Ohio’s 88 counties reporting over 400 congregate facility deaths each to date (Cuyahoga (753), Franklin (542), Montgomery (410) and Summit (462) Counties (Health, 2021).

In Cuyahoga County specifically as of 3/31/21, there have been 5478 cases among residents and 4255 cases among staff in 201 long-term care facilities (Health, 2021). There have also been 753 COVID-19 deaths attributed to long-term care facilities among 2003 total fatalities in the county, mirroring the 38% of fatalities in Ohio occurring among long-term care residents (Health, 2021; Terebuh et al., 2020).

As cases began to increase in Cuyahoga County in March of 2020, the CCBH COVID-19 response team recognized the significant number of individuals living in congregate settings who were susceptible to COVID-19. Such congregate sites included nursing homes, assisted living locations, intermediate care facilities and unlicensed group homes, mental health and substance abuse treatment centers, homeless shelters, and correctional facilities. Tracking, data management and response systems established for small infectious disease outbreaks at the local and state levels were insufficient for the task of identifying and serving the needs of the sites of these disease clusters. Despite very limited testing availability, COVID-19 cases within congregate sites increased, highlighting the critical importance of addressing mitigation efforts in these facilities. In particular a subset of these congregate sites―long-term care facilities (nursing homes, assisted living and intermediate care facilities)―are home to thousands of residents across the state, including many older adults and those with disabilities who have underlying medical and behavioral co-morbidities increasing their risks for complications and mortality from COVID-19 (Banerjee et al., 2020; Bernabeu-Wittel et al., 2021; Ecks, 2020; Lin, 2020; Mair et al., 2020; Marengoni et al., 2021; McQueenie et al., 2020; Tisminetzky et al., 2020).

As the large number of congregate cases developed, the physician response team pivoted into creating an infrastructure and support for multiple congregate facilities experiencing outbreaks. The physician team also managed a 24/7 phone line for cases and organizations to call with concerns or contact tracing questions, quickly developing expertise in the latest evidence around managing COVID-19.

In addition to a major focus on long-term care facilities and other congregate sites, the response team also identified high-risk patients and families who had been diagnosed with COVID-19, providing them with the public health physician call line, along with linkage to resources provided through our county emergency management partnership. As in other communities, those with limited resources were at high risk for severe complications from COVID-19, thus we sought to rapidly address pragmatic needs through home resource deliveries seven days a week (Bello-Chavolla et al., 2021). Registries were also created for various conditions conferring higher risk for complications related to COVID-19, in addition to an obstetrics registry of pregnant patients.

Case Study: Unimaginable and Unexpected Loss of Life

On March 20, 2020, we lost our first community member to COVID-19. I remember receiving the notification and then updating our state health department colleagues as this marked a grim milestone in our community and state’s fight against the virus. For the next 9 months, I carefully reviewed the daily reports of community residents who had succumbed to COVID-19. For me, this remains the most devastating part of the pandemic. Each person who has died as a result of COVID-19 is an irreplaceable member of our community with loved ones unable to grieve their loss in customary ways due to the virus. I vowed that each person lost in our jurisdiction would not be forgotten, but in their memory, our teams would continue to passionately press on doing everything in our power to prevent further loss of life. This unimaginable loss of life that has occurred so quickly and unexpectedly is an ever-present reminder of the magnitude and ferocity with which this virus ravaged our community and thousands of others across the globe. Lives have been unjustly cut short by this evolving pandemic and have disproportionately affected those most vulnerable due to structural and social determinants of health.

An equity lens and cultural humility foster new opportunities for community health.

In March 2020, CCBH employed a multi-pronged approach to the COVID-19 pandemic response that was grounded in equity which is a long-standing guiding principle of the Board’s population health work. Health equity, or the just and fair opportunity for everyone to achieve their optimal health, has been a guiding focus of CCBH’s work for the past decade, and has guided the multisector community health improvement plan for which CCBH has served as the backbone organization (HIP-Cuyahoga; World Health Organization, 2017). Thus, the foundation of this prior work in identifying and working toward conditions that foster health equity across Cuyahoga County, created a solid foundation on which to build the COVID-19 response. This also included engagement of long-time community partners with the shared vision of achieving health equity prior to the arrival of COVID-19.

This systemic equity focus was actualized in a number of ways. The physician hotline, while open to everyone, often served as a frontline for people who did not have a physician or medical home. We focused our testing and support services, and later vaccination efforts, on neighborhoods, congregate living settings, and demographic groups that often have been marginalized by traditional health care. When the hospital systems started becoming involved in nursing home mitigation efforts after a governor’s mandate, we focused on the smaller group homes and other congregate sites without formal hospital affiliations.

Case Study: Actualizing Cultural Humility and Cultural Safety

Over the course of the pandemic, the response team has encountered numerous multigenerational families who have experienced household spread, many of whom speak a native language other than English. In one such case, a Preventive Medicine resident who speaks the same language as the affected family was able to conduct case interviews and contact tracing. He was able to identify the index case and the location of spread, which included contacting that business and sharing guidance on cleaning and quarantine for exposed individuals. He also deduced that the family matriarch did not feel able to adhere to isolation orders because she felt committed to ensuring for the food needs of her extended family. Through negotiation in her native language, the physician and patient came to agreement that she would adhere to isolation if he could deliver culturally specific groceries to her home, which he did later that day, through support of the county emergency management team and the CCBH resource unit leader.

Systems thinking, balanced with on-the-ground work and relationships, make it possible to take on seemingly intractable problems.

The pandemic response strategy also employed a systems-thinking approach (Carey et al., 2015; Diez Roux, 2011; Hassan et al., 2020; Leischow et al., 2008; Midgley, 2003) while balancing an on-the-ground focus which moved beyond the tyranny of the moment to consider long-term proactive community needs in managing an ongoing pandemic. Within each phase of the pandemic response, the CCBH approach has been nested within other local, state and national contexts. The systems thinking approach involved considering the intersectionality of multiple community conditions with the arrival of COVID-19 and considering how to impact health for all through both transactional activities and systems level interventions described below.

As testing capacity slowly increased, our county hospital system, MetroHealth, robustly partnered with us to ensure an equity-grounded approach to testing that was explicitly community-based, rather than a narrow focus on their own patients and employees. They began by accepting samples from our PMR strike team, creating new workflows from drop-off through patient sample ordering and registration. Their generous approach to partnership in the pandemic is an exemplar in that they fully embraced the importance of caring for the most vulnerable in our community during a perilous time, offering their resources and support to stem spread of COVID-19 in the most high-risk locations. They additionally created a COVID-19 hotline which has functioned as a helpful bellwether for multiple community surges and has served thousands in our community with telehealth, testing and vaccination options.

To advance community health and equity, it is vital to meet both immediate needs and to focus on strategic efforts to transform systems and structures.

A long view empowers embattled people to move beyond the tyranny of the moment toward emergent opportunities. Phase 1 of the response included case identification and contact tracing in early March. After the first three Ohio cases were identified on March 9, 2020, within Cuyahoga County, the team identified workflows for case interviewing and contact tracing. This included identifying basic information about virus transmission, developing case definitions for lab-confirmed and probable cases, ensuring collection of accurate individual and population level data and implementing isolation and quarantine protocols. These workflows were conducted within the agency incident command structure and were continually refined in collaboration with other public health officials at the local and state levels, along with health care system colleagues. Contact tracing efforts became somewhat less complicated during the state-level stay-at-home order, but still required intensive interviewing and one-on-one contact with thousands of individuals. Additional information regarding our pandemic response with particular emphasis on congregate care settings can be found in the Appendix.

Quickly after developing initial workflows for case identification and contact tracing, the CCBH COVID-19 response team identified case clusters that began developing within congregate facilities. Despite limited testing in the early months of the pandemic, it became clear that long-term care facilities were among the highest risk locations for COVID-19 spread and adverse outcomes related to the virus. The CCBH team created an explicit focus on long-term care facilities, including assigning a lead Preventive Medicine physician to each cluster. The Preventive Medicine physicians including residents in training, quickly became more expert in this new illness and how to respond to it than more seasoned physicians who did not have their concentrated experience. Much about the illness was new, and learning focused on listening to the dozens and then hundreds of newly ill people to whom we were speaking, as well as constantly scanning the rapidly evolving world literature.

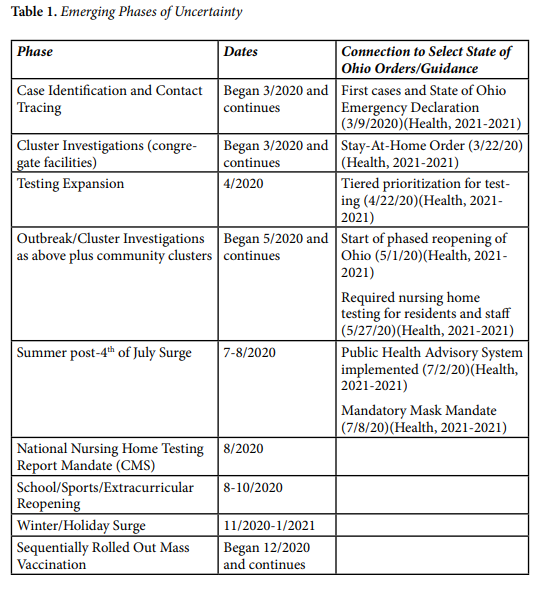

During the first few congregate setting outbreaks, it became clear that regular points of contact, known as strike team calls, were essential to partnering with congregate facilities to quickly minimize spread and loss of life. In partnership with the state epidemiologist and her team, we began to manage these calls at the local level and developed formalized protocols for initial and regular meetings with facilities to assist with outbreak management. These calls included state and other local partners to assist with situational awareness, deployment of resources and to maximize mitigation efforts efficiently. At points in the response, we were meeting with up to 10 facilities per day. We built capacity among our team to lead outbreak investigations and run these partner calls so that we could simultaneously serve multiple facilities at same time. Our public health incident command resource unit leader became the key point person in coordinating and communicating across the facilities. As identified in Table 1 (Appendix), the protocols became quite detailed and were iteratively improved and included information to guide strategic responses for the impacted facility and others that were potentially affected. We also intentionally led each meeting with the declaration that our intent was for partnership and support for as long as was necessary to control the outbreak.

Case Study: Unsung Extraordinary Leaders

One of the most impactful elements of the pandemic response has been the opportunity to learn about the hundreds of dedicated members of our community caring daily for vulnerable individuals within congregate settings. Due to the rapid spread of COVID-19, we quickly developed relationships with administrators, directors of nursing, small business owners, and many staff serving in congregate living settings across the county. We met selfless individuals who have dedicated their lives to ensuring aging individuals and those with disabilities live in safe, loving environments and are served by staff who care deeply about their ability to thrive. I learned a great deal and was inspired by visiting countless facilities to perform testing and partner on infection control and COVID-19 mitigation efforts. I learned about the networks of group homes and congregate sites, some public and others private, where individuals with disabilities are celebrated and lovingly cared for. While all of these leaders were under immense pressure due to COVID-19 cases, they readily partnered with our team to ensure those in their care and their employees were heroically protected and served in this unimaginable time. They challenge us to see the incredible resilience of thousands in our community who often go unnoticed, and provide inspiration to selflessly serve others every day, despite the cost.

In the early stages of the pandemic, testing also was terribly limited. This included minimal public health access to testing supplies, as well as personal protective equipment and staff to obtain samples in areas of highest concern. In response to these challenges, we pieced together a testing strategy with the assistance of multiple organizations and individuals in the community who generously donated supplies and time to fit test our team with a box of donated N-95 masks so that we could deploy into congregate settings and begin testing. PPE was donated from multiple sources, and we immediately instituted safe preservation procedures, not knowing if or when we would receive more PPE. Test kits were donated by local and state organizations, while we pieced together several thousand more by receiving swabs from one location, tubes from another, viral transport media made by another university and shipped directly to us, and sterile pipetting of that media into tubes by the CWRU media lab. Our community, and particularly the most vulnerable, needed testing, but because supplies and testing labs were not readily available, thus we resorted to partnerships, new and old, to bring together a full complement of testing supplies, PPE for the testing team, and lab access for COVID-19 testing.

For many months, the CCBH physician response unit quickly deployed testing teams to identified facilities to rapidly characterize the full scope of each outbreak and provide robust surveillance in the absence of ubiquitous community testing. The early weeks and months of the response included deploying teams, sometimes with only a few hours’ notice, to congregate settings with a plan for strategic testing among patients/residents and staff. Due to very limited testing capacity, we had to carefully review floorplans to conduct strategic surveillance to guide isolation and quarantine decisions for the entire congregate population.

The team also partnered with health department sanitarians to conduct environmental inspections and assist with real-time infection control guidance and health department communication experts to assist with stakeholder messaging and media coverage. A health department sanitarian and member of the physician response team worked together with congregate setting staff to identify areas of potential transmission throughout the facility, while also being continually available for consultation and guidance throughout the outbreak.

Case Study: Fear Abounds

In the early testing deployments of the physician response team to congregate living sites, which included nursing and group homes as well as homeless shelters, we encountered a great deal of fear, uncertainty and misinformation among nearly all involved stakeholders. We held improvised educational sessions with leaders, groups, and individuals. We frequently sent a team inside the building to test symptomatic patients/residents while another team worked outside to test employees in their cars while protecting privacy in whatever ways we could muster. These makeshift testing drive-throughs occurred throughout our community, sometimes on a daily basis in snow and rain, but were necessary to ensure rapid cessation of COVID-19 spread among the most vulnerable.

This early testing approach also included coordinating with our state health department on both the number of samples that could be tested and a means to deliver them three hours to the only lab at the time performing COVID-19 testing. Testing was limited for many months due to supply chain issues for test kits and reagents for the lab tests themselves to be run locally, thus we relied solely on the state public health lab infrastructure for an extended period of time.

We also often encountered distraught staff crying in their cars while waiting for testing, scared both of the actual procedure and of the result. We too were scared, worried if our PPE was adequate and whether we would ourselves become sick or bring this virus home to our families (Christ, 2021). I recall driving home in the dark after spending several hours at one of the first nursing homes where we tested and being overcome with emotion. The pain of the moment was visceral as my heart ached for the unexpected sadness, grief, and fear that gripped frontline workers and patients within congregate facilities so deeply affected by COVID-19. The staff were trying to communicate how much they loved their patients and residents and were doing all they could to keep them safe, but they mourned for those they had lost and those who had become ill. They also communicated how scared they were, sometimes with words and sometimes with a look through the window as we approached their car gowned up, only our eyes visible with a swab we were about to stick into their noses. I, too, was scared about the unknown. I knew the only option was to press forward daily in a race against time, using every public health tool we have, to protect our community and save lives through testing, case identification, contact tracing and mitigation efforts, but it was a perilous time, truly visible in facilities caring for those most vulnerable in our community.

Developing New Knowledge on the Ground Creates Opportunities for Broader Sharing.

The PMR and medical student teams quickly developed COVID-19 clinical and population level expertise given the high volume of cases and rapid evolution of the pandemic at the local level. Their on-the-ground knowledge quickly became a resource for local clinicians, leaders, and the public who had much less personal experience of seeing people with the emerging COVID-19 illness and who were desperate for grounded knowledge. While it was difficult to focus on anything other than the immediate and overwhelming needs of the response, we recognized the importance of sharing our evolving understanding and workflows. As a result, an important part of our strategy included connecting with others and sharing our evolving workflows and lessons learned for other communities who were beginning to see cases develop. Early lessons learned among the CCBH interprofessional teams, in partnership with long-term care facility staff, were channeled into toolkits that were readily shared on the CCBH website with other local health departments.

This sharing included frequent email and phone communication from medical schools and health departments within Ohio and surrounding states, but also included closely working with our state health department colleagues on developing just-in-time training for others. A PMR and medical student led a virtual training for contact tracers hired by the state, building on their expertise gained in the first few months of the pandemic. In conjunction with our county media team, we recorded and posted training videos on case interviewing, contact tracing, environmental inspections, nursing home and congregate setting outbreak investigation and mitigation measures. This included asking partners from local nursing homes to also record videos from their perspective to share guidance with others facing similar outbreaks. Finally, we continually revised our workflows and documents (with multiple language translations) which we continually updated on our website for others to freely use.

We also tried to steal a bit of time from the moment-to-moment immediate needs to write up some of the new observations that we had not seen in the emerging literature that we combed on a nearly daily basis. These include analyses of: characterization of community-wide transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in congregate living settings and our local public health-coordinated response during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic (Terebuh et al., 2020), gastrointestinal bleeding in SARS-CoV-2 infection (Fakolade et al., 2021), structural racism and risk of SARS-CoV-2 in pregnancy (Miracle et al., 2021; Pope et al., 2021), and the association of school instructional mode with community COVID-19 incidence (Terebuh et al., 2021).

Interprofessional Teams Enable Collective Action on a Complex Problem.

Within CCBH, there are public health professionals trained in many disciplines which provided robust expertise for tackling the pandemic response from multiple angles. These disciplines include environmental public health, epidemiology, informatics, dietetics, nursing, emergency preparedness, communications, community health, human resources, law, finance, and medicine, among many others. Over the course of the pandemic response, we focused on creating a culture where every member of the team could openly share their expertise and perspective and guide development of protocols and workflows grounded in both knowledge and experience. The entire team drew upon trust and social capital with each other inside and with partners outside the agency to operationalize nearly every aspect of our public health response. The future of public health must continue to prioritize trusting, authentic, long-term relationships in order to truly meet all essential functions of public health and ultimately impact population health and equity (Graham et al., 2013; Shadmi et al., 2020; Wojcik et al., 2020; Woolf, 2017).

Additionally, through an interprofessional approach, it is also clear that local congregate facility administrators and small business owners know their residents and are best positioned to drive community-based public health efforts within their own facilities. Through partnering with the interprofessional public health team, rapid mitigation efforts were deployed in dozens of facilities, averting further viral spread, morbidity and mortality. This emphasis on the value of local knowledge and the strength in an interprofessional approach to difficult situations is critically important as public health evolves as a result of COVID-19.

Transparency and Continuous Communication are Important Always--Vital in a Crisis.

From the outset of the pandemic response, we committed to a regular and transparent flow of information about COVID-19 in Cuyahoga County, creating channels of communication with multiple media partners at regular intervals. These press conferences, news articles and radio interviews provided an opportunity to share timely information with our community to ensure access to the latest updates on the impact of the pandemic on our local community and on efforts to mitigate the impact of COVID-19. Coordinated and consistent messaging also builds trust among community members and creates opportunities for additional partnerships and resources to be channeled where they are needed most. In Cuyahoga County, regular communication, which included our elected officials, created an opportunity to also discuss our community’s approach to racial equity and to simultaneously address both racial equity and COVID-19 in the wake of the national reckoning on racial justice.

Case Study: CCBH COVID-19 Press Briefing at the Intersection of Racial Inequities and COVID-19(Cuyahoga County COVID-19 Press Briefing; Speech starts at 20:31 minutes, 2020)

On June 5, 2020, we shared remarks regarding racism and its impact on our community. I shared the following remarks as context before providing the customary COVID-19 data update.

I cannot brief you on the status of the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on our community without first discussing the impact of the larger epidemic in this country that has killed far more people than coronavirus—that is racism. Racism has been a part of this country since the very beginning and is the root of profound differences in opportunity for people of color that lead to unjust, preventable health outcomes such as a high burden of chronic disease and early death. You’ve seen this week that thousands of individuals have exercised their first amendment rights to non-violently protest for racial justice in the wake of George Floyd’s murder.

We have worked here at CCBH with partners across the community for a number of years in HIP-Cuyahoga where in 2015, we first collectively declared eliminating structural racism and fostering racial equity shared priorities. That remains the cornerstone of our work as a community with stakeholders across many sectors who share the vision of making Cuyahoga County a place where everyone has an opportunity to reach their full potential. This is not a matter of right or left along the political spectrum, this is a matter of our shared humanity.

Today, though I want to share some insights from my own life as a native NE Ohioan, mother, and physician. I am white, which means that I was born with privilege. The privilege associated with being white is automatic given the context in which we live in the United States. I have seen images that look like me everywhere I look since I was very young. Products are designed for my skin color and hair type. I can do every day activities without fear of bias. As a white physician, I can walk just about anywhere in a hospital without being questioned. That is not the case for individuals of color here and in communities across our country.

It has long been time for those of us with privilege that confers us undeserved power to do the necessary and uncomfortable deep work of understanding, personally confronting and collectively eliminating racism, from implicit bias in our personal interactions and behavior to changing systems and policies that perpetuate structural racism and maintain our privilege. As a member of the dominant race, silence and inaction are not options. Every single one of us has a role to use our heart and minds in our spheres of influence to catalyze change. This requires transformation of our deeply engrained perspectives about race. This includes learning the historical roots of racial inequity in this country, not the sanitized version we learned in school, but the actual truth about this country’s history. As a first step, sign up for a Racial Equity Institute training—it will be 2 days that radically transform you. Build authentic relationships of mutual respect, predicated on trust that is earned over time with people who look different than you. Talk to your kids about racism now. Take a look at your workplace, your place of worship and the businesses you patronize—do the people there all look like you? Speak truth to power and take a stand for inclusion in those places regardless of the personal cost. Patronize businesses owned by people of color and those who are different from you. Listen to people of color, really listen to what they experience every single day and what those with this lived experience truly believe is necessary to move all of us as individuals, as a community and as a country to be better. These activities are just a few and certainly not sufficient, but they can be done right now and will begin to give you a glimpse into the everyday struggle of people of color in this country because of racism. The time is now to use your voice, your privilege, your power for real change.

I often hear from other white people that their lives have been hard. This conversation about racism in no way invalidates your experience of struggle in poverty or difficult circumstances. But what those who are white need to understand is that our struggles are not made more difficult by the color of our skin and we are afforded privileges we don’t even realize because we are so used to being in power even when we find ourselves in tough circumstances.

It will take all of us to work together collectively to change this community and our nation into a place where everyone has the opportunity to reach their full potential regardless of race, ethnicity, gender, religion, language, sexual orientation or any other non-majority demographic.

As a physician, I see firsthand the effects of the brokenness of this world through the privilege of partnering with patients in their lives. I frequently reflect that the issues contributing most intensely to poor physical and behavioral health are not actually anything I learned how to manage in medical school or residency, but rather they are issues of racism and poverty. Those are the actual causes of illness and death and those are very issues that we must work together to solve as individuals and as a collective community. It begins with each of us right now.

In my moment of gratitude today, I would like to conclude by thanking countless people who have influenced my personal perspective transformation journey around racism, helping me better understand their experience as people of color and my role as a white woman of privilege. I regret that I cannot name everyone here, but I want each of you to know how profoundly grateful I am for you spending time you didn’t have and that I didn’t deserve, to educate yet another white person about this issue. I cannot imagine how exhausting that must be day in and day out, but I am personally grateful for that sacrifice. I specifically wanted to mention two physician mentors at Wright State who guided me through medical school, Dr. Alonzo Patterson and Dr. Rhea Rowser, who believed in a naive white kid in her early 20s and spent a great deal of time personally pouring in to me. I also want to thank my long-time HIP-Cuyahoga co-chair, Greg Brown, a passionate servant in this community for many decades, who has so generously given of himself to catalyze my perspective transformation journey. Finally, I want to thank all of my patients, but particularly those of color who have given me a great deal of trust as a white doctor—trust I didn’t deserve and hadn’t earned, but which you so graciously gave. You have all taught me so very much and I thank you for your mentorship. These relationships and many others have transformed my life and my understanding of race and privilege and my role in fighting for change. Thank you for that eternal gift.

Beyond media communications, frequent contact with those most impacted by the pandemic was also critically important. As noted above, this came in the form of regular physician contact for patients who tested positive, but also for organizations managing outbreaks through our physician line, CCBH call center and outbreak investigation strike team calls.

Partnering with trusted community members to ensure open communication across the community is also critically important. With good reason, there is considerable mistrust of government by many community residents (Webb Hooper et al., 2019). This was evidenced by numerous instances where individuals receiving calls for case interviewing or contact tracing were suspicious of the caller and reluctant to cooperate with the public health interaction. This lack of trust is multifactorial, but addressing it became a critically important part of our response. Our team partnered with community health workers and other trusted neighborhood ambassadors, utilized multiple methods of communication, ensured assessment of the verbal and written preferred languages, partnered with interpreters and assessed for resource needs in each interaction, all approaches intended to quickly build rapport and provide public health care grounded in cultural humility.

In recent stages of the pandemic response, these communication efforts have focused simultaneously on the importance of continued mitigation efforts and testing given sustained high levels of community spread for nearly a year, coupled with the importance of rapidly vaccinating as many people as possible. Given a high degree of vaccine hesitancy we have experienced, especially among staff at congregate living facilities, an organized, equity-grounded communication strategy remains vital. The importance of continuous communication and long-standing, authentic relationships with trusted ambassadors of messaging on-the-ground must be critical components of future public health action.

Proactive Investment in Public Health Infrastructure Could Mitigate a Crisis.

At numerous points over the past year, we faced barriers to accomplishing public health control of COVID-19 in our local community due to fragmentation and a lack of a coordinated systems approach. Nationally there has been a systemic disinvestment in public health infrastructure over many decades (Institute of Medicine, 2012a, 2012b, 2015). The National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) characterizes public health infrastructure in the following categories: human, organizational, informational, legal, policy, and fiscal.

One powerful example of infrastructure challenge locally relates to data systems. Long-standing disinvestment in public health infrastructure at the federal and state levels has resulted in antiquated, separate data systems for tracking public health population metrics, infectious disease reports and vaccinations in Ohio. Furthermore, these systems have limited to no interoperability with health care system electronic medical records, private sector labs and records from congregate settings, both public and private.

Case Study: A Complex Web of Data

As the COVID-19 pandemic quickly unfolded, our team began to formulate a systems approach to the response. That task included identifying all sources of data and their potential utility in driving surveillance and mitigation approaches locally. In particular, this also included understanding the available data within congregate sites which were impacted hard and very early. We very quickly recognized an inconceivable patchwork of data types, sources and methods of transmission. Testing data began to flood the CCBH fax machine from multiple sources, while other cases were reported through the state disease reporting system. Still others were called in on the phone and many appeared to initially go unreported as many labs did not have connectivity to either the local or state health departments for direct reporting. Additionally, the systems designed for infectious disease reporting were siloed from vital statistics and vaccination systems, thus tracking and analyzing data from multiple elements of the response was tedious and often required substantial duplicative data entry and reconciliation. We worked closely with the internal informatics team, along with partner organizations and our state health department colleagues to both problem-solve and improve the current systems and craft longer-term more efficient solutions within the constraints of limited resources. In several studies, these fundamental data infrastructure challenges had profound impacts on the response for local and state health departments across the country (Holmgren et al., 2020; Madhavan et al., 2021).

As noted above, there must be an investment in data infrastructure among public health entities that also links with health care, social service and congregate care organizations in order to ensure rapid control of emerging infectious diseases. This lack of shared or even interoperable piecemealed data infrastructure locally has been a priority of the HIP-Cuyahoga consortium as it catalyzes efforts to present a comprehensive picture of the health of our community at regular intervals. Over the past year, however, the deleterious impacts have been even more apparent to the health of our community as testing, case investigation, contact tracing, and vaccination information was completely siloed in independent systems resulting in duplicative manual data entry and an inability to perform sophisticated public health analyses that could drive more efficient mitigation efforts.

Policy Implications

The Imperative of an Equity Lens

In order to focus resources where they are most needed and can have the most impact, local public health organizations must employ an equity lens that includes considerations of age, disability and congregate housing status as well as the upstream drivers of inequities in these demographics. Traditionally, efforts to improve population health occur in silos with public health and health care systems working independently to improve conditions in their own spheres of influence (Institute of Medicine, 2016). Such efforts often focus downstream rather than on the upstream systems and structures that profoundly impact the health of the most vulnerable. The experiences in COVID-19, in particular in attempting to protect those most vulnerable from the mortality and morbidity of this novel virus, demonstrate that to be most impactful and proactive, organizations must share a language and common commitment to equity as a driving force for population health work. In our community, we have been fortunate to have over 10 years of capacity building around health equity and a common vocabulary among key partners through our cross-sector HIP-Cuyahoga consortium. This long-term investment in equity capacity-building created a strong foundation on which to build the pandemic response.

Using a Systems Approach for Cross-Sector Action

An equity-grounded approach also includes sharing a systems method to catalyze cross-sector action where the outcome of health for the community is shared by those who are part of a larger whole than their own individual organizations. We live, work, learn and play in complex dynamic systems and the structures of those systems lead to behavior of the system, including feedback cycles, that impact people in profound ways (Kaplan et al., 2017). Sometimes these cycles are vicious and sometimes they are virtuous, but understanding the intersectionality in parts of the system and our interdependence and shared humanity, is critically important (Sturmberg et al., 2021).

Additionally, there are multiple advantages to working with organizations of varying size and structure in the public, not-for-profit and private sectors, but also within different fields (Shen, 2008). Each organization has different capacities, cultures, spheres of influence, and nimbleness, thus potentially providing key unique elements of larger whole in a community level response, particularly one this large (Hamer & Mays, 2020). In the case of Cuyahoga County, this involved multiple levels of municipal and county governments, philanthropic partners, not-for-profit organizations within and outside of public health and health care and many others to ensure a wide variety of community needs were met over the past year. This partnership built on our systems and equity work within HIP-Cuyahoga (HIP-Cuyahoga) along with robust, pre-existing relationships grounded in trust built over time working on other initiatives. This solid foundation and systems approach provided the opportunity for both individuals or organizations to see how their work and influence is part of a larger effort and a community-level response.

Reinvention of Public Health

“Public health is what we do together as a society to ensure the conditions in which everyone can be healthy” (Public Health 3.0: A Call to Action to Create a 21st Century Public Health Infrastructure). Public health organizations exist to deliver on this vision for public health, however some health departments also have a teaching mission as well (Erwin & Keck, 2014).

Prior to COVID-19, the governmental public health community was in the process of reinventing the future of public health in an effort known as Public Health 3.0. This effort is focused on 5 themes: strong leadership and workforce, strategic partnerships, flexible and sustainable funding, timely and locally relevant data, metrics, and analytics, and foundational infrastructure. Additionally, Healthy People 2030 and NACCHO both have recommendations and resources related to public health transformation and infrastructure investment (Healthy People 2030: Public Health Infrastructure, 2021; Public Health 3.0: A Call to Action to Create a 21st Century Public Health Infrastructure).

COVID-19 has profoundly highlighted major fissures in the US public health system at all levels: local, state, tribal, territorial and federal levels. While local and state governments are still grappling with the major impacts of COVID-19, there is a precious opportunity to redesign and adequately fund a public health infrastructure that truly meets the vision of creating opportunities for everyone to thrive and live their healthiest lives. This must include investments in thoughtful infrastructure planning in all five areas noted above at all levels in order to sustainably improve population health and tackle the most profound drivers of health inequities.

This redesign must occur now at the local, state and federal levels before the next crisis and should be focused on investments in data systems with interoperability across the continuum of care, authentic trusted relationships particularly with those most impacted by health inequities, and a workforce prepared to employ systems thinking and catalyze change in dynamic environments. A recent declaration by the President of the American Medical Association acknowledges the critical need in this moment for both a declaration and commitment of investment in public health infrastructure, calling on health care institutions to be part of the solution for this critical problem (Bailey, 2021).

Prevention is the Priority

There are 4 levels of prevention: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary. Typically, health care focuses on tertiary prevention, or minimizing the impact of disease once it is already clinically apparent. The most severe COVID-19 outcomes occurred in those with underlying co-morbidities, including older age and chronic disease like diabetes. Care provided in the tertiary prevention realm is often costly and less impactful at the population level. Public health however typically focuses on primary or secondary prevention with efforts such as vaccinations, healthy eating/active living and screening for conditions such as cancer and lead poisoning. Efforts in these areas are cost-effective and highly impactful at the population level.

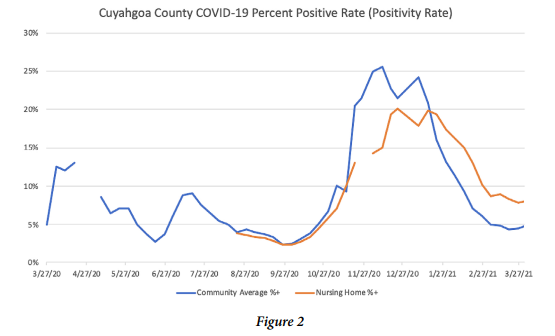

Additionally, coordination and commitment to prevention across all levels of governmental public health is also critically important to ensure equitable population health outcomes. Several examples of federal focus on primary and secondary prevention include the national pharmacy vaccination program among congregate care facilities and commercial pharmacies, as well as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid services public reporting of congregate care facility testing volumes and results (Appendix) (Nursing Home Data - COVID-19 Test Positivity Rates, 2021). This enabled us locally to track this measure of community spread as another key metric in understanding the scope of impact at the local level.

As is evident from the impacts of COVID-19, collaborative focus of both health care and public health on primary and secondary prevention in the form of mitigation efforts, population level policies for universal masking and social distancing, and vaccination provide tremendous promise in minimizing community spread and subsequent morbidity and mortality. Thus, future efforts in both sectors must focus on collaborative upstream prevention, ultimately leading to improved downstream community outcomes that occur with a shorter pandemic and healthier population.

Recognition of and Action to Address Structural Inequities

As the nation grapples with the impacts of over 400 years of racism superimposed on the COVID-19 pandemic, the impact of structural determinants of health has become more readily apparent (Laurencin & McClinton, 2020; Lin, 2020). In addition to the impacts of structural racism, there are other structural determinants of health and powerful forms of bias that have created health inequities for many populations including those who are older and disabled. Future policy directions at the local, state and federal levels, must account for past injustices rooted in oppressive policy and build in extra support for those most proximal to the impacts of inequities. As an example, populations most impacted by morbidity and mortality from COVID-19 such as black and brown communities, older adults, those with disabilities and residents of congregate facilities should be prioritized first for COVID-19 vaccination.

The Ohio vaccine prioritization plan led by the state health department in collaboration with the Governor’s office, focused on older adults and those in congregate settings first based on prior COVID-19 impact data. In the fourteen weeks since the first COVID-19 vaccinations in Ohio, 55% of nearly 3.4 million vaccinations started have occurred in Ohioans age 60 or older as compared with earlier data from week four which showed 91% of vaccines initiated were among Ohioans 60 and older (Health, 2021). As of the end of March, 65% of all completed series in Ohio were given to those age 60 and older (Health, 2021). This approach to primary prevention of COVID-19 is the result of recognition of the marked impact on older adults and those in congregate settings early in the pandemic.

Integration between Public Health and Primary Care

The utter devastation of COVID-19 among vulnerable populations and the rising tsunami of evolving chronic disease related to the virus demands that organizations move beyond a coordination of efforts between public health and clinical care, to intentional integration of infrastructure and mission. Public health and medicine were historically separated with many driving forces behind the divergence of both fields (Brandt & Gardner, 2000; Shahid et al., 2020). However, the COVID-19 pandemic has proven that the two are inextricably linked and efforts over the next few years at both local and national levels must focus on meaningful integration of the two fields. In particular, there must be widespread investment in currently under-funded and under-appreciated public health and primary care infrastructure and workforce initiatives (Geyman, 2021; Kidd, 2020; Westfall et al., 2020). This integration is vital as thousands of people move from acute COVID-19 infection to the morbidity associated with chronic impacts. Layered mitigation strategies must include partnership between local health departments and health care systems in order to seamlessly provide care across the continuum.

Considerations for Older Adults

The devastating impact of COVID-19 on older adults in local communities and those across the world provides a critical illustration of the importance of focusing on multiple policy spheres that address health and equity. Emerging evidence from the pandemic points to chronological age alone as a risk factor for poor outcomes from COVID-19 at the individual level (Nidadavolu & Walston, 2021; Shahid et al., 2020; Verdery et al., 2021), but other considerations such as long-term care policies, quality and accessibility of health care, and community conditions also appear to have marked impact on morbidity and mortality for older adults (Bello-Chavolla et al., 2021). In order to ensure equity in outcomes for older adults, focus on the individual, population and structural or systems levels is imperative.

At both the individual and community levels, investment in relationships is critically important to promote health and well-being, but also for behavioral and physical health risk mitigation in the midst of a pandemic (Whitehead & Torossian, 2021). Such relationships include patient, caregiver, primary care and other healthcare team members, and community partners and should be grounded in a life course perspective which helps all stakeholders work together to address emerging challenges that seem impossible when working in isolation, but which are solvable when working together. Furthermore, the application of systems thinking is essential to considering the impact of context on health outcomes, including the high degree of interdependency between individuals and among community resources (Hassan et al., 2020).

At the population level during a crisis, it is essential to first think about the most vulnerable community members and ensure that an equity lens is applied to a range of policy provisions, including resource allocation. It is also essential to use new knowledge deficits as the impetus for systematically developing and disseminating broad new knowledge. This also requires a commitment to broad communication and investment in a shared vision that supports the collective and explicitly focuses on the most vulnerable, including older adults and those with disabilities.

Finally at the systems level, adequate data infrastructure is necessary to ensure policy decisions are evidence-based and focused on equitable population level outcomes. In the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, the quality of population level data available to adequately investigate the impact of various risk factors on older adults is lacking at local, state, and national levels and has resulted in markedly inadequate data analytic capabilities necessary to understand risk and potential solutions for ameliorating the pandemic impact on older adults at both the individual and population levels (Verdery et al., 2021). This is particularly concerning given the continued evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic with an apparent emerging threat of breakthrough infections disproportionately affecting older adults and potentially due in part due to variant spread related to vulnerabilities in exposure, such as through low vaccination rates among caregivers. To date in the US, 75% of those who are hospitalized or die from breakthrough infections (confirmed COVID-19 infection ³ 14 days after vaccination) have occurred in those ³ 65 years of age (Prevention, 2021). Integrated data systems that facilitate the bidirectional exchange of information and analytic capabilities between public health, clinical care entities, and community organizations is vital to minimizing further morbidity and mortality and creating nimble community level responses to the needs of older adults and other vulnerable populations. Multiple levels of health policy focus on data accessibility and integration is key to ensuring equitable outcomes for older adults.

Conclusion

The pandemic reminds and informs us that:

The impact of COVID-19 on older adults and those with disabilities living in long-term care facilities both locally and throughout the US is indisputable. The lessons learned from focusing a local public health response on these areas of highest need are transportable to other communities and also to future crises that may occur locally. Shortage can engender creativity to solve clinical and population health problems in context despite limited resources. Balancing the tension between individual autonomy and the collective good is necessary to advance population health. A strong commitment to foster equity and ensure community systems where everyone has an opportunity to thrive must be a guiding force for transformation as we collectively move out of the transactional tyranny of the moment caused by COVID-19 and begin to rebuild our communities together. While the pandemic has caused irreparable devastation in families and communities throughout the world, there are clear lessons learned amidst the darkness that are cause for much hope, not the least of which are the countless servants within congregate care facilities who have devoted their lives to the service of others.

Acknowledgements

I am profoundly grateful to the many patients, community residents, and leaders, as well as public health, health care, and social service partners whose selfless work amidst fear and uncertainty provided the inspiration for this article. I am thankful for the mentorship of Health Commissioner Terry Allan and my HIP-Cuyahoga partner, Greg Brown. I appreciate the support of my family during so many long hours working on the pandemic response, and am grateful to Dr. Kahana, an anonymous reviewer, and to Dr. Kurt Stange for helpful critiques of earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland, KL2TR002547 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) component of the National Institutes of Health, and by a Fellowship from The Institute for Integrative Health.

References

10 Essential Public Health Services. (Updated 2020). https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/publichealthservices/essentialhealthservices.html

Bailey, S. (2021). Pandemic exposes dire need to rebuild public health infrastructure https://www.ama-assn.org/about/leadership/pandemic-exposes-dire-need-rebuild-public-health-infrastructure

Banerjee, A., Pasea, L., Harris, S., Gonzalez-Izquierdo, A., Torralbo, A., Shallcross, L., . . . Hemingway, H. (2020). Estimating excess 1-year mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic according to underlying conditions and age: a population-based cohort study. Lancet, 395(10238), 1715-1725. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30854-0

Bello-Chavolla, O. Y., González-Díaz, A., Antonio-Villa, N. E., Fermín-Martínez, C. A., Márquez-Salinas, A., Vargas-Vázquez, A., . . . Gutiérrez-Robledo, L. M. (2021). Unequal impact of structural health determinants and comorbidity on COVID-19 severity and lethality in older Mexican adults: Considerations beyond chronological aging. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 76(3), e52-e59. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glaa163

Bernabeu-Wittel, M., Ternero-Vega, J. E., Nieto-Martín, M. D., Moreno-Gaviño, L., Conde-Guzmán, C., Delgado-Cuesta, J., . . . Ollero-Baturone, M. (2021). Effectiveness of a on-site medicalization program for nursing homes with COVID-19 outbreaks. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 76(3), e19-e27. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glaa192

Brandt, A. M., & Gardner, M. (2000). Antagonism and Accommodation: Interpreting the relationship between public health and medicine in the United States during the 20th century. American Journal of Public Health, 90(5), 707-715.

Bureau, U. C. (2019). Cuyahoga County. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/cuyahogacountyohio,US/PST045219

Carey, G., Malbon, E., Carey, N., Joyce, A., Crammond, B., & Carey, A. (2015). Systems science and systems thinking for public health: a systematic review of the field. BMJ Open, 5(12), e009002. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009002

Christ, G. (2021). Health care workers balance protecting family, serving community during coronavirus pandemic. https://www.cleveland.com/metro/2020/03/health-care-workers-balance-protecting-family-serving-community-during-coronavirus-pandemic.html

Cuyahoga County Board of Health. (2020). Covid-19 Information. Retrieved February 9, 2021 from https://www.ccbh.net/coronavirus/

Cuyahoga County COVID-19 Press Briefing; Speech starts at 20:31 minutes. (2020). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5bNSuYwbgMo&list=PLRv4vNBXmfaeD3cYUsTEHT9Ac5TcslyoT&index=19

Diez Roux, A. V. (2011). Complex systems thinking and current impasses in health disparities research [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. Am J Public Health, 101(9), 1627-1634. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300149

Ecks, S. (2020). Multimorbidity, polyiatrogenesis, and COVID-19. Med Anthropol Q, 34(4), 488-503. https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.12626

Erwin, P. C., & Keck, C. W. (2014). The Academic Health Department: The Process of Maturation. J Public Health Management and Practice, 20(3), 270-277.

Fakolade, A. O., Gullett, H., Egwiekhor, A., Miracle, J., Ganesh, P., Rose, J., & Stange, K. C. (2021). Gastrointestinal Bleeding in SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Med Science Case Reports, 8(e928822). https://doi.org/10.12659/MSCR.928822

Geyman, J. P. (2021). Beyond the COVID-19 pandemic: The urgent need to expand primary care and family medicine. Fam Med, 53(1), 48-53. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2021.709555

Gorgulu, O., & Duyan, M. (2020). Effects of comorbid factors on prognosis of three different geriatric groups with COVID-19 diagnosis. SN Compr Clin Med, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-020-00645-x

Graham, R., McCann, M., & Allen, N. (2013). Public health managers: ambassadors, coordinators, scouts, or guards? J Public Health Manag Pract, 19(6), 562-568. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182902384

Gullett, H. (2021). Students as Patient Navigators: Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine. In Value-Added Roles for Medical Students. Elsevier.

Hamer, M. K., & Mays, G. P. (2020). Public health systems and social services: Breadth and depth of cross-sector collaboration. Am J Public Health, 110(S2), S232-S234. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305694

Hassan, I., Obaid, F., Ahmed, R., Abdelrahman, L., Adam, S., Adam, O., . . . Kashif, T. (2020). A Systems Thinking approach for responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. East Mediterr Health J, 26(8), 872-876. https://doi.org/10.26719/emhj.20.090

Health, O. D. o. (2021). COVID-19 Data Dashboard. https://coronavirus.ohio.gov/wps/portal/gov/covid-19/dashboards/overview

Healthy People 2030: Public Health Infrastructure. (2021). https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/public-health-infrastructure

HIP-Cuyahoga. HIP-Cuyahoga. Retrieved March 30, 2021 from https://hipcuyahoga.org/

Holmgren, A. J., Apathy, N. C., & Adler-Milstein, J. (2020). Barriers to hospital electronic public health reporting and implications for the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 27(8), 1306-1309.

Institute of Medicine. (2012a). For the Public's Health: Investing in a Healthier Future. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/doi:10.17226/13268

Institute of Medicine. (2012b). Primary Care and Public Health: Exploring Integration to Improve Population Health. National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine. (2015). Financing Population Health Improvement: Workshop Summary. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18835

Institute of Medicine. (2016). Collaboration Between Health Care and Public Health: Workshop Summary. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/21755

Kaplan, G. A., Diez Roux, A. V., Simon, C. P., & Galea, S. (2017). Growing Inequality: Bridging Complex Systems, Population Health, and Health Disparities. Westphalia Press.

Kidd, M. R. (2020). Five principles for pandemic preparedness: Lessons from the Australian COVID-19 primary care response. Br J Gen Pract, 70(696), 316-317. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp20X710765

Laurencin, C. T., & McClinton, A. (2020). The COVID-19 Pandemic: a Call to Action to Identify and Address Racial and Ethnic Disparities. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00756-0

Leischow, S. J., Best, A., Trochim, W. M., Clark, P. I., Gallagher, R. S., Marcus, S. E., & Matthews, E. (2008). Systems thinking to improve the public's health. Am J Prev Med, 35(2 Suppl), S196-203.

Lin, S. L. (2020). Intersectionality and inequalities in medical risk for severe COVID-19 in the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Gerontologist. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa143

Madhavan, S., Bastarache, L., Brown, J. S., Butte, A. J., Dorr, D. A., Embi, P. J., . . . Ohno-Machado, L. (2021). Use of electronic health records to support a public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States: a perspective from 15 academic medical centers. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Asssociation, 28(2), 393-401.

Mair, F. S., Foster, H. M., & Nicholl, B. I. (2020). Multimorbidity and the COVID-19 pandemic - An urgent call to action. J Comorb, 10, 2235042X20961676. https://doi.org/10.1177/2235042X20961676

Marengoni, A., Zucchelli, A., Vetrano, D. L., Armellini, A., Botteri, E., Nicosia, F., . . . Onder, G. (2021). Beyond chronological age: Frailty and multimorbidity predict in-hospital mortality in patients with Coronavirus disease 2019. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 76(3), e38-e45. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glaa291

McQueenie, R., Foster, H. M. E., Jani, B. D., Katikireddi, S. V., Sattar, N., Pell, J. P., . . . Nicholl, B. I. (2020). Multimorbidity, polypharmacy, and COVID-19 infection within the UK Biobank cohort. PLoS One, 15(8), e0238091. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238091

Midgley, G. (Ed.). (2003). Systems Thinking. Sage Publications.

Miracle, J., Ganesh, P., Rose, J., Terebuh, P., Wolfe, H., Stange, K., . . . Pope, R. (2021). COVID-19 in Pregnancy: Occupations with Higher Density of Population Exposure Associated with More Severe Disease. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (Accepted for Publication).

Nidadavolu, L. S., & Walston, J. D. (2021). Underlying vulnerabilities to the Cytokine Storm and adverse COVID-19 outcomes in the aging immune system. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 76(3), e13-e18. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glaa209

Nursing Home Data - COVID-19 Test Positivity Rates. (2021). https://data.cms.gov/stories/s/COVID-19-Nursing-Home-Data-Test-Positivity-Rates/q5r5-gjyu

Ohio Department of Health COVID-19 Mortality Data. (2021). Retrieved March, 31, 2021 from https://coronavirus.ohio.gov/wps/portal/gov/covid-19/dashboards/long-term-care-facilities/mortality

Pope, R. J., Ganesh, P., Miracle, J., Brazile, R., Honor, W., Rose, J., . . . Gullett, H. (2021). Structural racism and risk of SARS-CoV-2 in pregnancy. EClinicalMedicine, 100950. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100950

Prevention, C. f. D. C. a. (2021). Hospitalized or Fatal COVID-19 Vaccine Breakthrough Infections. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/health-departments/breakthrough-cases.html

Public Health 3.0: A Call to Action to Create a 21st Century Public Health Infrastructure. https://www.naccho.org/uploads/downloadable-resources/Public-Health-3.0-White-Paper.pdf

Shadmi, E., Chen, Y., Dourado, I., Faran-Perach, I., Furler, J., Hangoma, P., . . . Willems, S. (2020). Health equity and COVID-19: global perspectives. Int J Equity Health, 19(1), 104. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-01218-z

Shahid, Z., Kalayanamitra, R., McClafferty, B., Kepko, D., Ramgobin, D., Patel, R., . . . Jain, R. (2020). COVID-19 and Older Adults: What We Know. J Am Geriatr Soc, 68(5), 926-929. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16472

Shen, B. (2008). Toward cross-sectoral team science. Am J Prev Med, 35(2 Suppl), S240-242.

Sturmberg, J. P., Getz, L. O., Stange, K. C., Upshur, R. E. G., & Mercer, S. W. (2021). Beyond multimorbidity: What can we learn from complexity science? J Eval Clin Pract. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.13521

Terebuh, P., Albert, J., Curtis, J., Stange, K. C., Hrusch, S., Brennan, K., . . . Rose, J. (2021). Association of School Instructional Mode with Community COVID-19 Incidence During August – December 2020 in Cuyahoga County, Ohio. J. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses (under review).

Terebuh, P. D., Egwiekhor, A. J., Gullett, H. L., Fakolade, A. O., Miracle, J. E., Ganesh, P. T., . . . Allan, T. (2020). Characterization of community-wide transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in congregate living settings and local public health-coordinated response during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Influenza Other Respir Viruses, Oct 15:10.1111/irv.12819 Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1111/irv.12819

Tisminetzky, M., Delude, C., Hebert, T., Carr, C., Goldberg, R. J., & Gurwitz, J. H. (2020). Age, multiple chronic conditions, and COVID-19: A literature review. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glaa320

Verdery, A. M., Newmyer, L., Wagner, B., & Margolis, R. (2021). National profiles of Coronavirus disease 2019 mortality risks by age structure and preexisting health conditions. The Gerontologist, 61(1), 71-77. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa152

Webb Hooper, M., Mitchell, C., Marshall, V. J., Cheatham, C., Austin, K., Sanders, K., . . . Grafton, L. L. (2019). Understanding multilevel factors related to urban community trust in healthcare and research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(18), 3280.

Westfall, J. M., Liaw, W., Griswold, K. S., Stange, K. C., Green, L. A., Phillips, R., . . . Gotler, R. S. (2020). Uniting Public Health and Primary Care for Healthy Communities in the COVID-19 Era and Beyond. Am J Pub Health (under review).

Whitehead, B. R., & Torossian, E. (2021). Older adults’ experience of the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed-methods analysis of stresses and joys. The Gerontologist, 61(1), 36-47. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa126

Wojcik, O., Miller Mshp, C. E., & Plough, A. L. (2020). Aligning health and social systems to promote population health, well-being, and equity. Am J Public Health, 110(S2), S176-S177. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305831

Woolf, S. H. (2017). Progress in achieving health equity requires attention to root causes. Health Aff (Millwood), 36(6), 984-991. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0197

World Health Organization. (2017). 10 facts on health inequities and their causes. Retrieved August 2, 2019 from https://www.who.int/features/factfiles/health_inequities/en/

Wynants, L., Van Calster, B., Bonten, M. M. J., Collins, G. S., Debray, T. P. A., De Vos, M., . . . van Smeden, M. (2020). Prediction models for diagnosis and prognosis of covid-19 infection: systematic review and critical appraisal. BMJ, 369, m1328. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1328

Appendix

Figure 1. CCBH Outbreak Investigation Congregate Facility Strike Team Call Template

ii.Ruled out for Influenza A/B, RSV

iii.Other considerations – U/A, CXR