Racial Differences in Self-Appraisal, Religious Coping, and Psychological Well-being in Later Life During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Timothy Goler, PhD, Tirth Bhatta, PhD, Nirmala Lekhak, PhD, and Neema Langa, MA

|

Download article:

|

| ||

ABSTRACT

Older adults from minority groups, especially those with pre-existing health conditions, have been generally considered the most vulnerable to the COVID-19. Due to greater health disadvantages prior to the pandemic, its adverse health impact in terms of mortality has been disproportionately higher on Blacks than Whites. The existing health disadvantages and worsening economic conditions due to the pandemic are likely to be anxiety-inducing that could adversely impact the mental health of Black older adults. Existing studies conducted in the pre-pandemic era have documented paradoxical findings on race differences in later life psychological well-being. Even with significant structural disadvantages, Black older adults tended to report significantly better psychological well-being (e.g., lower depressive symptoms) than White adults. The racial differences in coping mechanisms have been cited as an explanation for such paradoxical findings. Based on our national web-based survey (n=1764, aged 50 years or older), we examined race differences in coping resources such as religious coping and self-appraisal and their impacts on anxiety and depressive symptoms. We documented greater concerns about the personal impacts of the pandemic among Blacks than their White counterparts. The greater concerns about the pandemic were associated with poorer psychological well-being outcomes. Yet Blacks reported fewer depressive symptoms and lower anxiety than Whites. Our study finds subjective religiosity, religious coping, and emotional support to be responsible for better psychological well-being among Blacks than Whites. Our study highlights policy implications of coping resources for racial differences in later life psychological well-being.

Keywords: Health Disparities, Global Life Event, Public Policy, Suppressed Inequality

Older adults from minority groups, especially those with pre-existing health conditions, have been generally considered the most vulnerable to the COVID-19. Due to greater health disadvantages prior to the pandemic, its adverse health impact in terms of mortality has been disproportionately higher on Blacks than Whites. The existing health disadvantages and worsening economic conditions due to the pandemic are likely to be anxiety-inducing that could adversely impact the mental health of Black older adults. Existing studies conducted in the pre-pandemic era have documented paradoxical findings on race differences in later life psychological well-being. Even with significant structural disadvantages, Black older adults tended to report significantly better psychological well-being (e.g., lower depressive symptoms) than White adults. The racial differences in coping mechanisms have been cited as an explanation for such paradoxical findings. Based on our national web-based survey (n=1764, aged 50 years or older), we examined race differences in coping resources such as religious coping and self-appraisal and their impacts on anxiety and depressive symptoms. We documented greater concerns about the personal impacts of the pandemic among Blacks than their White counterparts. The greater concerns about the pandemic were associated with poorer psychological well-being outcomes. Yet Blacks reported fewer depressive symptoms and lower anxiety than Whites. Our study finds subjective religiosity, religious coping, and emotional support to be responsible for better psychological well-being among Blacks than Whites. Our study highlights policy implications of coping resources for racial differences in later life psychological well-being.

Keywords: Health Disparities, Global Life Event, Public Policy, Suppressed Inequality

Introduction

In America, the racial climate confronting Blacks is one where race and racism are dominant features of American Society (e.g., Militarized police forces, violence not seen in the United States since 1968, and the denial of civil rights). Blacks have been in a condition of social instability rooted in America’s history and sustained through public policies and social norms. Racialized social systems perpetuate the vicious cycles of stressful life events for Blacks, experienced on a daily basis, which puts their health at risk. Racial differences in later life health disparities in the United States have been well documented (Brondolo et al., 2009). A leading cause of these disparities is the greater exposure to stress among minorities across the life course (Kavachi et al., 2005). Studies confirm that racial minority status combined with poorer SES circumstances magnify negative health outcomes (Williams, 1997; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2000; Williams et al., 2008). For decades, Blacks have endured higher rates of diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and asthma as compared to their White counterparts. Converging at the same time is the coronavirus pandemic, which at this time has killed more than 525,875 people in America (National Center for Health Statistics, 2021). COVID-19 cases in the U.S. are climbing again, and data shows that Blacks are contracting and dying at higher rates than White Americans (Oppel et al., 2020). According to the National Center for Health Statistics, 76,608 Blacks have lost their lives to COVID-19 to date. Blacks have 1.4 times higher rates of dying than Whites (The COVID Tracking Project, 2021). Grounded in a stress and coping framework, this study provides a fuller depiction of how individuals who have experienced structural disadvantage in a pandemic maintain well-being. Based on our national web-based survey (n=1764, aged 50 years or older), we examine race differences in coping resources such as religious coping and self-appraisal and their role in explaining racial differences in anxiety and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Racial Differences in Psychological Well-being Prior to the Pandemic

Racial differences in psychological well-being among older adults in the United States have been well documented (Krause & Chatters, 2005; Ellison, 2017; Nguyen et al., 2018; Chatters et al., 2018; Taylor, 2020). Prior to the pandemic, a substantial number of studies have obtained paradoxical findings when examining race differences in various psychological well-being outcomes such as overall life satisfaction and depressive symptoms. Despite significant structural disadvantages (e.g., higher levels of poverty, discrimination) that are documented to adversely impact mental health, Blacks report lower prevalence rates in most mood and anxiety disorders than non-Latino Whites (Taylor & Chatters, 2020; Mezuk et al., 2013; Gallo et al., 1998). While a significant number of studies have suggested better psychological well-being outcomes among Black older adults relative to Whites, existing studies have also reported better psychological well-being among Whites than their Black counterparts (Mouzon et al., 2016). Based on the Health and Retirement Survey of individuals 50 years and older living in the United States, a study by Ayalon and Gum (2011) found significantly greater levels of life satisfaction and lower levels of depressive symptoms among Whites than Blacks. Given the disproportionate impacts of COVID on the Black community, it is unclear whether the aforementioned racial differences in well-being outcomes will be maintained amidst the pandemic.

Racial Differences in Coping Resources

Black older adults are experiencing devastating consequences of the pandemic due to significantly greater existing structural disadvantages than their White counterparts. The disadvantaged circumstances of the COVID-19 are a continuation of the historical legacy of unequal social and economic institutional mechanisms that were designed to undervalue and oppress Black Americans (Robinson-Dooley & Wade-Berg, 2015). Black older adults experience “double jeopardy” as a result of both racism and ageism, and that, in effect, puts them at a significantly higher risk of coronavirus exposure and death (Chatters et al., 2020). These challenges could result in the intensification of immense stress exposure due to the pandemic (Cobb, 2021) that, in the absence of buffers, can manifest in poor psychological well-being (Kahana et al., 2014). In such context, it is salient to examine the significance of widely reported racialized coping mechanisms such as religious coping and self-appraisal for racial differences in psychological well-being. Our study explores whether previously documented disproportionately higher coping resources such as religious coping and social support among Black older adults continue to positively influence their psychological well-being during the pandemic.

Existing evidence shows greater subjective religiosity among Blacks than Whites (Nguyen, 2020; Assari et al., 2018). A recent Pew survey showed that 97 percent of Blacks believe in God or a higher power, relative to 90 percent among non-Black respondents. Similarly, 59 percent agreed that religion was “very important” to them compared to 40 percent non-Black respondents agreeing to the same (Besheer et al., 2021). Krause et al. (2005) claimed that the beliefs and values shaped and shared in religious congregations provide resources for religious coping responses that may help in dealing with life problems, especially in later life. Subjective religiosity has been repeatedly associated with better mental and emotional well-being, including less depression, suicide, coping with stress, and negatively associated with a host of other risk factors across health indicators (Lukachko et al., 2015; Villani et al., 2019; Nguyen, 2020; Davenport et al., 2021). In the context of subjective religiosity, religious coping is a racialized coping mechanism made within a unique set of structural constraints of the Black experience in America. Religious coping has been identified as a coping resource that may impact a person’s experience with stress (Ano & Vasconcelles, 2005; Ward, 2010). Subjective religiosity has been found to be one of the most salient ways for Blacks to cope with structural disadvantages and race-related stressors (Taylor et al., 2004). The positive effects of religious coping on the psychological well-being of Black Older Adults also reinforce an underlying assumption of the social role of the “Black Church” on psychological well-being.

Studies have also shown that historically, the Black church has been a place of protection and escape from negative environmental conditions (Nguyen, 2020). Researchers have referred to the bond between Black families and the church as an “enduring institution” (Berry & Blassingame, 1982; Stephanson & West, 1989). Cornell West (1989) called the contemporary African American church “one of the few institutions within a shattered Black civil society that could attempt to project some kind of hope and some kind of meaning” in the face of present and more pervasive “walking nihilism.” Despite restrictions on gathering due to the pandemic, Black Churches operating in a new normal (e.g., online worship services) are continuing to be a source of support for Blacks (Garcia et al., 2020; Barber & Kim, 2021).

The unique life experiences among Blacks could contribute to their appraisal of life circumstances differently from that of White adults. Mental acts such as appraisal, perceiving, attending, remembering, framing, generalizing, classifying, and interpreting (in other words, “thinking”) are always performed by specific individuals with certain personal cognitive idiosyncrasies affecting the thinking and behavior of Blacks (Smith & Zerubavel, 2010). Findings suggest older Blacks experience greater exposure to chronic stressors but appraise stressors as less upsetting relative to whites (Brown et al., 2018). Experiences of individual and institutional racism coupled with lower socioeconomic positioning are likely to shape the individual cognitive appraisal process of Blacks, such that they evaluate later life well-being against the backdrop of continued adversity that they have experienced over the life course. Our study undertakes an important step in understanding the role of the aforementioned racialized coping resources in impacting racial differences in later life psychological well-being during the pandemic.

Data and Methods

We used data from our “Coping with Coronavirus Pandemic Study,” which is a cross-sectional national web-based survey of adults 50 years or older who reside in the United States. Our survey was administered from April 7 to June 15, 2020, to understand how older adults living in the United States are affected by and coping with coronavirus pandemic. We adopted a non-probability sampling technique to recruit study participants from social media and senior centers. Our recruitment approach allowed any eligible individual with a reasonable understanding of the English language to participate in the survey. We advertised our survey using social media (primarily Facebook) and other communication platforms (e.g., emails to different senior service organizations). We used our personal social media accounts to extend the invitation to participate in the survey or share the survey information among their networks. We created social media pages (Facebook page: “Coronavirus Study”; Twitter handle: @StudyCorona) to increase awareness about our study further. The information about the survey was also shared in public social media groups (e.g., Las Vegas Coronavirus group) and included in newsletters of professional organizations (e.g., Gerontological Society of America, American Sociological Association). Finally, paid advertisements were created in social media outlets such as Facebook and Twitter to target our potential study participants.

Respondents were able to access the survey questionnaire only after they consented to proceed beyond a participant information page. On that page, we included a brief description of our study and explained any potential harm or discomfort that they might encounter. We did not offer any incentive or reward for their participation. We collected anonymous responses from participants using an electronic survey method called Qualtrics, which was then downloaded into an encrypted file on the researcher’s computer. Our survey was granted an exemption by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Measures

We used two psychological well-being outcomes as our dependent variables: depressive symptoms and anxiety.

Coping Resources

We used self-appraisal of COVID pandemic, religious coping, subjective religiosity, and emotional support as coping resources.

Sociodemographic and Health Characteristics – We coded race (1=Black, 0=White), gender (1 = female, 0 = male), and marital status (1 = married, 0 = not married) into two categories. Age was measured in years as a continuous variable. Income was divided into 11 ordinal categories that ranged from 1 (less than $10,000) to 11 ($100,000 and above). Education was coded into six ordinal categories: 1 (=No High School and GED), 2 (=High School graduate), 3 (=Some College), 4 (= Bachelor’s degree), 5 (= Master’s degree) and 6 (=Doctorate degree). Functional Limitations were measured by a 4-item PROMIS Physical Function scale. We asked respondents to evaluate their ability to perform activities of daily living (e.g., “Are you able to run errands and shop?”) on a five-point scale. Their responses (range: from 1 =without any difficulty to 5=unable to do) were summed to create functional limitations score for each respondent. Chronic Diseases were measured by summing binary responses on 15 diagnosed health conditions (e.g., arthritis, angina, diabetes, asthma, stroke, and hypertension).

Analyses

Our statistical analyses began by first examining the distribution of study variables. We calculated descriptive statistics such as proportion, mean, and standard deviation. Second, we performed bivariate statistical tests to assess the relationship between race and coping resources. We conducted t-tests to examine racial differences in self-appraisal, emotional support, subjective religiosity, and religious coping. Finally, we fitted ordinary least square (OLS) regression models to investigate the relationship between racial status and psychological well-being. We adjusted for sociodemographic and health characteristics because of the widely reported racial differences in socioeconomic status and health outcomes. Subsequently, we assessed the role of coping resources in explaining the relationship between racial status and psychological well-being. Such assessment was made by including coping resource variables in the first regression model.

Results

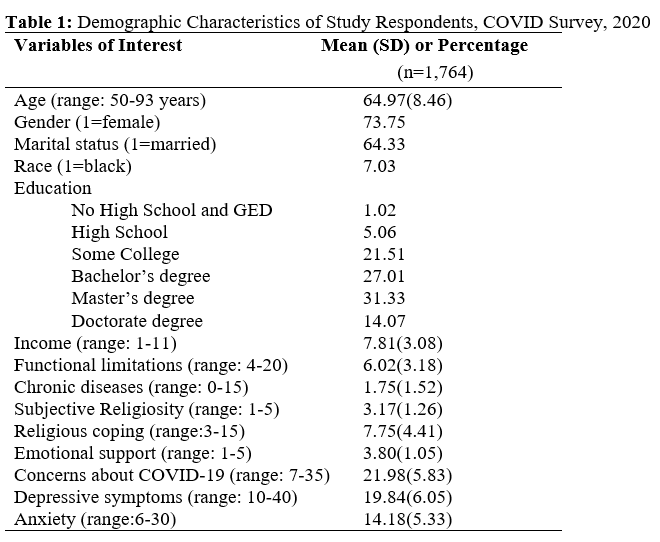

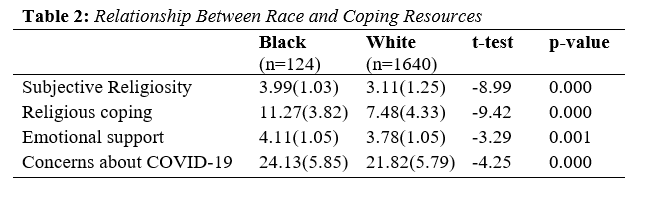

As shown in Table 1, the average age of respondents was 65 years. About 74 percent of respondents were women, and seven percent of them were Blacks. A great majority of respondents (72.41%) had a bachelor’s degree or higher education. Only 18 percent reported their household income to be less than $40,000 per year. Our examination of racial differences in coping resources is presented in Table 2. The appraisal of the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of personal implications significantly differed between Black and White adults. Black adults expressed significantly greater concerns (t=-4.25, p=0.000) about coronavirus pandemic than White adults. We find significantly greater subjective religiosity (t=-8.99, p=0.000) and use of religious coping (t=-9.42, p=0.000) among Black adults relative to their White counterparts. Relative to Whites, significantly greater receipt of emotional support (t=-3.29, p=0.001) was also documented among Black adults.

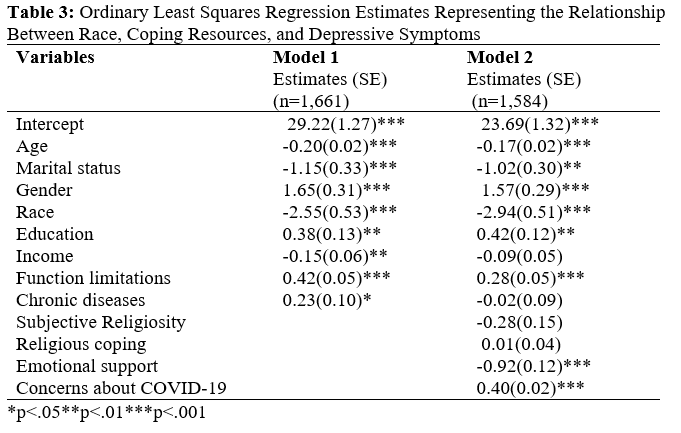

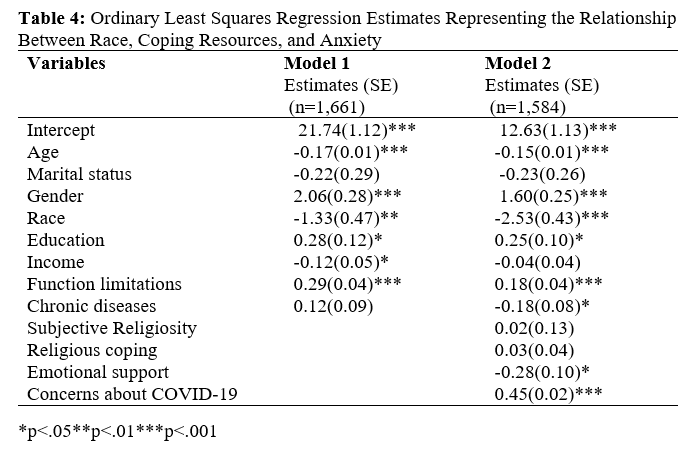

Our results from regression analyses (presented in Tables 3 and 4) help us examine racial differences in depressive symptoms and anxiety. Even after adjusting for demographic and health characteristics, Model 1 shows significantly fewer depressive symptoms (β=-2.55, p<0.001) and lower anxiety (β=-1.33, p<0.001) among Black adults than their White counterparts. The racial differences in both psychological well-being outcomes narrowed (Depressive symptoms: β =-1.84, p<0.01; Anxiety: β =-1.29, p<0.05) when three coping resources (subjective religiosity, religious coping, and emotional support) were included in our regression analysis (not reported in Table). Greater distribution of those coping resources and their positive impact on psychological well-being outcomes explained fewer depressive symptoms and lower anxiety among Black adults.

Our regression analysis also suggests that receipt of emotional support independently influences psychological well-being. In other words, individuals (regardless of their race and other characteristics adjusted in our regression analysis) who report receipt of greater emotional support also have significantly fewer depressive symptoms (β=-0.92, p<0.001) and lower anxiety (β=-0.28, p<0.05). As Model 2 shows, the self-appraisal of the COVID-19 pandemic did not explain why Black adults report better psychological well-being than White adults. That is likely due to their greater concerns about the pandemic, which seems to contribute significantly higher depressive symptoms (β= 0.40, p<0.001) and anxiety (β=0.45, p<0.001). The significant lower depressive symptoms and anxiety among Black adults than their White counterparts was still maintained even after the influence of coping resources has been accounted for.

Discussion

Our study takes an important step in identifying the psychological resources that have unique salience for the mental health of Black older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., a serious global health threat). We offer unique insights into the racial differences in later life psychological well-being in the era of COVID-19 pandemic and the role of coping resources in mediating those racial differences. Studies conducted prior to the pandemic generally found better psychological well-being among Black adults relative to Whites. Despite having disproportionately greater structural risk factors (e.g., institutional racism, poverty, residential segregation) for poor mental health outcomes, Black older adults tend to report lower anxiety and higher life satisfaction than their White counterparts (Taylor & Chatters, 2020). Consistent with those studies, Blacks report better psychological well-being despite their greater concerns about the personal impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

We documented significantly higher depressive symptoms and anxiety among individuals with greater concerns about the pandemic. These negative psychological well-being outcomes may reflect the impact of experiences of social isolation and concerns about economic security due to a destabilized labor market (Gauthier et al., 2020). Our study finds that Black adults appraise the COVID-19 pandemic to have significantly greater personal implications than the appraisal reported by White adults. The greater concerns about the coronavirus pandemic reflect the psychological impact of longstanding disparities in health conditions for Blacks in the United States. Fannie Lou Hamer, the great civil rights activist, expressed her health and economic challenges during similar tumultuous times by saying, “I’m Sick and Tired of Being Sick and Tired,” which also conveys the current health and economic conditions faced by far too many Blacks trying to cope with COVID-19. Our findings of racial differences in the appraisal of personal implications of COVID-19 differ from previous studies on self-appraisal. Existing research has reported that Blacks consider stressors as less upsetting than Whites. The inconsistency in findings could be due to differences in the type of stressors that people have been asked to appraise. Previous studies tend to ask people to appraise individual-level events (e.g., life events) (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Turner & Wheaton, 1995; Cohen et al. 2019; Park & George, 2013) than a global event that our study does. Self-appraisal is likely to be racially mediated (Williams et al., 1997). The stressfulness of a life experience is determined, in part, by the meaning it has for the individual. The appraisal of an event is linked to an individual’s personal and social history, which differ across racial groups. Blacks appraise an individual-level stressor against the backdrop of adverse life events that they have experienced over the life course, but the same dynamic may not apply to a global pandemic.

Our findings underscore the need to consider the unique role of racialized coping resources in shaping disparities in later life psychological well-being. Despite their concerns, Black adults report fewer depressive symptoms and lower anxiety than White adults. Our findings indicate that better psychological well-being among Black adults could be due to coping resources such as emotional support, subjective religiosity, and religious coping. These coping resources may help them counteract the concerns they have about the pandemic. Similar to existing studies, we find that individuals with positive emotions, such as receiving greater emotional support, have fewer depressive symptoms and lower anxiety (Kahana et al., 2021).

Our study finds subjective religiosity and religious coping to be among the most salient ways for Blacks to cope with structural disadvantages. The positive effects of religious coping on the psychological well-being of Black older adults reinforce an underlying assumption of the social role of the “Black Church” on psychological well-being. The Black church and religion have played a prominent role in Blacks’ lives (Blank et al., 2002; Barnes, 2013). The Black church has offered a space to form a faith-based community, the relevance of which continues beyond the church. Faith has been at the heart of the Black community’s struggle for survival and is recounted in historical and contemporary writings (Romero, 2005). Faith-based perspectives, such as biblical admonitions of “man shall not live by bread alone; and “The word of God is, health to the bone and marrow of those who find it,” are important values, attitudes, and beliefs for Blacks that helps us to understand why Blacks in our study despite existing health disadvantages and worsening economic conditions due to the pandemic are concerned but report lower depressive symptoms and less anxiety than whites.

Resilience and Denial

Despite considering the influence of religious coping, subjective religiosity, and emotional support, Blacks continue to report significantly fewer depressive symptoms and anxiety. Resilience and denial may explain why Black older adults are less anxious and depressed than whites during a pandemic. For over 400 years since the first documented arrival of Africans who came to America by way of Point Comfort, Va. in August 1619, they have been exposed to unimaginable brutality of slavery, ensuing historical eras such as Reconstruction and Jim Crow, and continuing racial oppression (Wyatt-Nichol & Seabrook, 2016). These experiences have all reinforced among Blacks an emphasis on overcoming obstacles against all odds (Becker & Newson, 2005). Such emphasis contributed to the adaptation of a resilience philosophy rooted in their long struggle for freedom and equality. Breznitz (1983) has suggested that stress and denial go hand in hand; in extreme forms, denial can be pathological. Lazarus and Folkman (1984) suggest denial-like processes used as coping mechanisms might adversely affect psychological health status. For example, the perilous effects of racism could lead to maladaptive coping, such as engaging in alcohol and drug abuse, violence, self-blame, suicide, and remaining in denial.

According to Breznitz, sometimes denial can save us from breaking under strain. Some degree of denial may help to maintain a belief in a “just world” and the fairness of others, avoid feelings of powerlessness and vulnerability and conserve emotional energy, blocking out the negativity of any kind (Crosby, 1984; Harrell, 2000). Those who deny their distress have been found to report higher degrees of happiness and life satisfaction (Johnson & Crowley, 1996). The denial of stress among Blacks may reflect their socialization in the tradition of an African-American folk hero named “John Henry.” Having a “John Henry” personality is symbolic of some Black people who try to overcome all odds, no matter what the obstacles, even though denying the existence of real problems that may be insurmountable can lead to detrimental health outcomes (Lincoln et al., 2003). We speculate that even though Blacks are concerned about the COVID-19, they deny negative thoughts or emotions about the impact COVID-19 could have on them, leading to lower depressive symptoms and anxiety than whites.

Policy Implications

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed huge health inequalities in the U.S. The disproportionate COVID-19 related deaths among racial and ethnic minorities reflect the unequal burden of pre-existing health conditions. Greater concerns about COVID-19 among Blacks relative to their White counterparts is likely driven by their material disadvantages in terms of income, wealth, and health. Our findings point to the urgent need for policies that will mitigate concerns of racial and ethnic minorities, especially those experiencing financial hardship in the US. They indicate a need for macro-level policies that attempt to reduce the disproportionate burden of COVID-19 among racial and ethnic groups with a greater risk of infection, hospitalization, and death. The policies should be designed to address both the immediate crisis and the possible long-term implications. State and local legislators should forge a partnership with local clinics, hospital systems, faith-based institutions, and community organizations to help those grieving the loss of loved ones to COVID-19. Care should be given to creating institutional mechanisms that can offer culturally sensitive support services and interventions to help them cope with the various stressors (e.g., job loss, death of a family member) caused by pandemic. In addition to the disturbing loss of lives among Blacks, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused massive economic pain. Congress should continue to provide cash benefits and unemployment reliefs. This will provide them additional coping resources to lessen their concerns, thereby reducing their adverse impacts on psychological well-being outcomes.

Our study documented that Blacks are more likely to utilize religious coping when dealing with a stressful situation. At an individual level, the reliance on religious coping could help them adapt to the adverse circumstances created by the COVID-19 pandemic. Such reliance may not, however, alleviate the stress of job loss or a stressful work environment. They may say they are “too blessed to be stressed,” but underlying that statement may hide the suffering they are going through because of economic conditions or other structural problems. We call this phenomenon “suppressed inequality” because such cognitive denial is likely to mask mental health disparities. The denial, emanating from continued exposure to the oppression of opportunity, resources, power, results in minimizing any negative emotional experiences. An individual from oppressed and exploited groups could become so used to hiding stress caused by adverse material circumstances that they don’t even recognize their own feelings because they have dismissed them for so long. Such denial could lead to the minimization of potential mental health issues, and that, coupled with the lack of health care coverage, could discourage them from seeking help from mental health professionals. Excessive reliance on religious coping could contribute to the positive evaluation of psychological health, which then runs the risk of suppressing racial inequalities in mental health. Without demanding structural solutions to alleviate pain and suffering due to stressful material conditions, the situation of potentially suppressed racial disparities in mental health is likely to remain unchanged.

Limitations

Despite significant scholarly and policy implications, we are cognizant of the limitations of our study. Black participants in the study are underrepresented in proportion to the population of Black Americans in the U.S. (7% in the sample vs. 13% of the U.S. population). Given the nature of our data collection (i.e., the non-probability sample obtained from web-based survey), the likelihood of self-selection bias is unavoidable. Our sample has a higher percentage of women and very low participation of individuals with no education and less than high school education. We recognize that disproportionate representation of women and higher educated individuals is likely to bias our findings and make it less likely to be generalizable to the larger population of the United States. Our measure of emotional support could be improved by future studies. The measure of emotional support used in our study combines support from family, friends, and neighbors, making it difficult to distinguish the sources of social support, and their potentially differential impacts on psychological well-being.

Acknowledgement: This work was supported by funding from the Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing Zeta Kappa-At-Large Chapter.

In America, the racial climate confronting Blacks is one where race and racism are dominant features of American Society (e.g., Militarized police forces, violence not seen in the United States since 1968, and the denial of civil rights). Blacks have been in a condition of social instability rooted in America’s history and sustained through public policies and social norms. Racialized social systems perpetuate the vicious cycles of stressful life events for Blacks, experienced on a daily basis, which puts their health at risk. Racial differences in later life health disparities in the United States have been well documented (Brondolo et al., 2009). A leading cause of these disparities is the greater exposure to stress among minorities across the life course (Kavachi et al., 2005). Studies confirm that racial minority status combined with poorer SES circumstances magnify negative health outcomes (Williams, 1997; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2000; Williams et al., 2008). For decades, Blacks have endured higher rates of diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and asthma as compared to their White counterparts. Converging at the same time is the coronavirus pandemic, which at this time has killed more than 525,875 people in America (National Center for Health Statistics, 2021). COVID-19 cases in the U.S. are climbing again, and data shows that Blacks are contracting and dying at higher rates than White Americans (Oppel et al., 2020). According to the National Center for Health Statistics, 76,608 Blacks have lost their lives to COVID-19 to date. Blacks have 1.4 times higher rates of dying than Whites (The COVID Tracking Project, 2021). Grounded in a stress and coping framework, this study provides a fuller depiction of how individuals who have experienced structural disadvantage in a pandemic maintain well-being. Based on our national web-based survey (n=1764, aged 50 years or older), we examine race differences in coping resources such as religious coping and self-appraisal and their role in explaining racial differences in anxiety and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Racial Differences in Psychological Well-being Prior to the Pandemic

Racial differences in psychological well-being among older adults in the United States have been well documented (Krause & Chatters, 2005; Ellison, 2017; Nguyen et al., 2018; Chatters et al., 2018; Taylor, 2020). Prior to the pandemic, a substantial number of studies have obtained paradoxical findings when examining race differences in various psychological well-being outcomes such as overall life satisfaction and depressive symptoms. Despite significant structural disadvantages (e.g., higher levels of poverty, discrimination) that are documented to adversely impact mental health, Blacks report lower prevalence rates in most mood and anxiety disorders than non-Latino Whites (Taylor & Chatters, 2020; Mezuk et al., 2013; Gallo et al., 1998). While a significant number of studies have suggested better psychological well-being outcomes among Black older adults relative to Whites, existing studies have also reported better psychological well-being among Whites than their Black counterparts (Mouzon et al., 2016). Based on the Health and Retirement Survey of individuals 50 years and older living in the United States, a study by Ayalon and Gum (2011) found significantly greater levels of life satisfaction and lower levels of depressive symptoms among Whites than Blacks. Given the disproportionate impacts of COVID on the Black community, it is unclear whether the aforementioned racial differences in well-being outcomes will be maintained amidst the pandemic.

Racial Differences in Coping Resources

Black older adults are experiencing devastating consequences of the pandemic due to significantly greater existing structural disadvantages than their White counterparts. The disadvantaged circumstances of the COVID-19 are a continuation of the historical legacy of unequal social and economic institutional mechanisms that were designed to undervalue and oppress Black Americans (Robinson-Dooley & Wade-Berg, 2015). Black older adults experience “double jeopardy” as a result of both racism and ageism, and that, in effect, puts them at a significantly higher risk of coronavirus exposure and death (Chatters et al., 2020). These challenges could result in the intensification of immense stress exposure due to the pandemic (Cobb, 2021) that, in the absence of buffers, can manifest in poor psychological well-being (Kahana et al., 2014). In such context, it is salient to examine the significance of widely reported racialized coping mechanisms such as religious coping and self-appraisal for racial differences in psychological well-being. Our study explores whether previously documented disproportionately higher coping resources such as religious coping and social support among Black older adults continue to positively influence their psychological well-being during the pandemic.

Existing evidence shows greater subjective religiosity among Blacks than Whites (Nguyen, 2020; Assari et al., 2018). A recent Pew survey showed that 97 percent of Blacks believe in God or a higher power, relative to 90 percent among non-Black respondents. Similarly, 59 percent agreed that religion was “very important” to them compared to 40 percent non-Black respondents agreeing to the same (Besheer et al., 2021). Krause et al. (2005) claimed that the beliefs and values shaped and shared in religious congregations provide resources for religious coping responses that may help in dealing with life problems, especially in later life. Subjective religiosity has been repeatedly associated with better mental and emotional well-being, including less depression, suicide, coping with stress, and negatively associated with a host of other risk factors across health indicators (Lukachko et al., 2015; Villani et al., 2019; Nguyen, 2020; Davenport et al., 2021). In the context of subjective religiosity, religious coping is a racialized coping mechanism made within a unique set of structural constraints of the Black experience in America. Religious coping has been identified as a coping resource that may impact a person’s experience with stress (Ano & Vasconcelles, 2005; Ward, 2010). Subjective religiosity has been found to be one of the most salient ways for Blacks to cope with structural disadvantages and race-related stressors (Taylor et al., 2004). The positive effects of religious coping on the psychological well-being of Black Older Adults also reinforce an underlying assumption of the social role of the “Black Church” on psychological well-being.

Studies have also shown that historically, the Black church has been a place of protection and escape from negative environmental conditions (Nguyen, 2020). Researchers have referred to the bond between Black families and the church as an “enduring institution” (Berry & Blassingame, 1982; Stephanson & West, 1989). Cornell West (1989) called the contemporary African American church “one of the few institutions within a shattered Black civil society that could attempt to project some kind of hope and some kind of meaning” in the face of present and more pervasive “walking nihilism.” Despite restrictions on gathering due to the pandemic, Black Churches operating in a new normal (e.g., online worship services) are continuing to be a source of support for Blacks (Garcia et al., 2020; Barber & Kim, 2021).

The unique life experiences among Blacks could contribute to their appraisal of life circumstances differently from that of White adults. Mental acts such as appraisal, perceiving, attending, remembering, framing, generalizing, classifying, and interpreting (in other words, “thinking”) are always performed by specific individuals with certain personal cognitive idiosyncrasies affecting the thinking and behavior of Blacks (Smith & Zerubavel, 2010). Findings suggest older Blacks experience greater exposure to chronic stressors but appraise stressors as less upsetting relative to whites (Brown et al., 2018). Experiences of individual and institutional racism coupled with lower socioeconomic positioning are likely to shape the individual cognitive appraisal process of Blacks, such that they evaluate later life well-being against the backdrop of continued adversity that they have experienced over the life course. Our study undertakes an important step in understanding the role of the aforementioned racialized coping resources in impacting racial differences in later life psychological well-being during the pandemic.

Data and Methods

We used data from our “Coping with Coronavirus Pandemic Study,” which is a cross-sectional national web-based survey of adults 50 years or older who reside in the United States. Our survey was administered from April 7 to June 15, 2020, to understand how older adults living in the United States are affected by and coping with coronavirus pandemic. We adopted a non-probability sampling technique to recruit study participants from social media and senior centers. Our recruitment approach allowed any eligible individual with a reasonable understanding of the English language to participate in the survey. We advertised our survey using social media (primarily Facebook) and other communication platforms (e.g., emails to different senior service organizations). We used our personal social media accounts to extend the invitation to participate in the survey or share the survey information among their networks. We created social media pages (Facebook page: “Coronavirus Study”; Twitter handle: @StudyCorona) to increase awareness about our study further. The information about the survey was also shared in public social media groups (e.g., Las Vegas Coronavirus group) and included in newsletters of professional organizations (e.g., Gerontological Society of America, American Sociological Association). Finally, paid advertisements were created in social media outlets such as Facebook and Twitter to target our potential study participants.

Respondents were able to access the survey questionnaire only after they consented to proceed beyond a participant information page. On that page, we included a brief description of our study and explained any potential harm or discomfort that they might encounter. We did not offer any incentive or reward for their participation. We collected anonymous responses from participants using an electronic survey method called Qualtrics, which was then downloaded into an encrypted file on the researcher’s computer. Our survey was granted an exemption by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Measures

We used two psychological well-being outcomes as our dependent variables: depressive symptoms and anxiety.

- Depressive symptoms – We used 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD-R 10) to measure depressive symptoms. The scale items aimed to capture the frequency of specific emotions (e.g., “felt depressed”) during a week, with the responses ranging from 1 (=rarely or none of the time) to 4 (=all of the time). High Cronbach’s α (=0.88) suggests that items used to assess depressive symptoms were strongly inter-related. The response across ten items was summed to create depressive symptoms score for each respondent.

- Anxiety – We used a 6-item PROMIS Emotional Distress-Anxiety scale to measure anxiety during the pandemic. We assessed respondent’s emotional status during the pandemic by asking them to evaluate statements such as “I felt fearful.” The responses were recorded on a 5-point scale, with responses ranging from 1(=never) to 5(=very often). High Cronbach’s α (=0.93) indicates strong inter-relationships among scale items administered to assess anxiety. We summed responses across six items to create an anxiety score for each respondent.

Coping Resources

We used self-appraisal of COVID pandemic, religious coping, subjective religiosity, and emotional support as coping resources.

- Concerns about COVID-19 – We used our 7-item scale to assess respondent’s appraisal of the personal implications of the COVID pandemic. Some of the questions that respondents were asked include: “To what extent, are you concerned about coronavirus affecting you personally? Do you feel you can protect yourself from coronavirus infection? Are you concerned about dying from coronavirus? Are you concerned about financial hardship from coronavirus pandemic?” The responses were recorded on a 5-point scale from 1 (= not at all) to 5 (= very much). Scale items were strongly inter-related as indicated by high Cronbach α (= 0.82). We summed responses across seven items to construct a score that represented each respondent’s concerns about COVID-19.

- Subjective religiosity was evaluated by asking respondents, “How religious do you consider yourself?” The response was measured on a five-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (= not at all religious) to 5 (=very religious).

- Religious coping – We used three items from the Carver Ways of Coping Scale to assess the extent to which respondents use religion to handle stressful situations (Carver 1989). Specifically, the respondents were asked: When I am confronted with stress, 1. “I seek God’s help” 2. “I put my trust in God” 3. “I try to find comfort in my religion.” Their responses were recorded on a five-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (= not at all) to 5 (= very often). Cronbach’s α (=0.96) demonstrates excellent interrelationship among scale items. The responses across three items were summed to create a religious coping score for each respondent.

- Emotional Support – We measured emotional support by asking respondents, “How emotionally supportive have family, friends, or neighbors been to you during the coronavirus pandemic?” Their responses were recorded on a scale of 1 (=none) and 5 (=very much).

Sociodemographic and Health Characteristics – We coded race (1=Black, 0=White), gender (1 = female, 0 = male), and marital status (1 = married, 0 = not married) into two categories. Age was measured in years as a continuous variable. Income was divided into 11 ordinal categories that ranged from 1 (less than $10,000) to 11 ($100,000 and above). Education was coded into six ordinal categories: 1 (=No High School and GED), 2 (=High School graduate), 3 (=Some College), 4 (= Bachelor’s degree), 5 (= Master’s degree) and 6 (=Doctorate degree). Functional Limitations were measured by a 4-item PROMIS Physical Function scale. We asked respondents to evaluate their ability to perform activities of daily living (e.g., “Are you able to run errands and shop?”) on a five-point scale. Their responses (range: from 1 =without any difficulty to 5=unable to do) were summed to create functional limitations score for each respondent. Chronic Diseases were measured by summing binary responses on 15 diagnosed health conditions (e.g., arthritis, angina, diabetes, asthma, stroke, and hypertension).

Analyses

Our statistical analyses began by first examining the distribution of study variables. We calculated descriptive statistics such as proportion, mean, and standard deviation. Second, we performed bivariate statistical tests to assess the relationship between race and coping resources. We conducted t-tests to examine racial differences in self-appraisal, emotional support, subjective religiosity, and religious coping. Finally, we fitted ordinary least square (OLS) regression models to investigate the relationship between racial status and psychological well-being. We adjusted for sociodemographic and health characteristics because of the widely reported racial differences in socioeconomic status and health outcomes. Subsequently, we assessed the role of coping resources in explaining the relationship between racial status and psychological well-being. Such assessment was made by including coping resource variables in the first regression model.

Results

As shown in Table 1, the average age of respondents was 65 years. About 74 percent of respondents were women, and seven percent of them were Blacks. A great majority of respondents (72.41%) had a bachelor’s degree or higher education. Only 18 percent reported their household income to be less than $40,000 per year. Our examination of racial differences in coping resources is presented in Table 2. The appraisal of the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of personal implications significantly differed between Black and White adults. Black adults expressed significantly greater concerns (t=-4.25, p=0.000) about coronavirus pandemic than White adults. We find significantly greater subjective religiosity (t=-8.99, p=0.000) and use of religious coping (t=-9.42, p=0.000) among Black adults relative to their White counterparts. Relative to Whites, significantly greater receipt of emotional support (t=-3.29, p=0.001) was also documented among Black adults.

Our results from regression analyses (presented in Tables 3 and 4) help us examine racial differences in depressive symptoms and anxiety. Even after adjusting for demographic and health characteristics, Model 1 shows significantly fewer depressive symptoms (β=-2.55, p<0.001) and lower anxiety (β=-1.33, p<0.001) among Black adults than their White counterparts. The racial differences in both psychological well-being outcomes narrowed (Depressive symptoms: β =-1.84, p<0.01; Anxiety: β =-1.29, p<0.05) when three coping resources (subjective religiosity, religious coping, and emotional support) were included in our regression analysis (not reported in Table). Greater distribution of those coping resources and their positive impact on psychological well-being outcomes explained fewer depressive symptoms and lower anxiety among Black adults.

Our regression analysis also suggests that receipt of emotional support independently influences psychological well-being. In other words, individuals (regardless of their race and other characteristics adjusted in our regression analysis) who report receipt of greater emotional support also have significantly fewer depressive symptoms (β=-0.92, p<0.001) and lower anxiety (β=-0.28, p<0.05). As Model 2 shows, the self-appraisal of the COVID-19 pandemic did not explain why Black adults report better psychological well-being than White adults. That is likely due to their greater concerns about the pandemic, which seems to contribute significantly higher depressive symptoms (β= 0.40, p<0.001) and anxiety (β=0.45, p<0.001). The significant lower depressive symptoms and anxiety among Black adults than their White counterparts was still maintained even after the influence of coping resources has been accounted for.

Discussion

Our study takes an important step in identifying the psychological resources that have unique salience for the mental health of Black older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., a serious global health threat). We offer unique insights into the racial differences in later life psychological well-being in the era of COVID-19 pandemic and the role of coping resources in mediating those racial differences. Studies conducted prior to the pandemic generally found better psychological well-being among Black adults relative to Whites. Despite having disproportionately greater structural risk factors (e.g., institutional racism, poverty, residential segregation) for poor mental health outcomes, Black older adults tend to report lower anxiety and higher life satisfaction than their White counterparts (Taylor & Chatters, 2020). Consistent with those studies, Blacks report better psychological well-being despite their greater concerns about the personal impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

We documented significantly higher depressive symptoms and anxiety among individuals with greater concerns about the pandemic. These negative psychological well-being outcomes may reflect the impact of experiences of social isolation and concerns about economic security due to a destabilized labor market (Gauthier et al., 2020). Our study finds that Black adults appraise the COVID-19 pandemic to have significantly greater personal implications than the appraisal reported by White adults. The greater concerns about the coronavirus pandemic reflect the psychological impact of longstanding disparities in health conditions for Blacks in the United States. Fannie Lou Hamer, the great civil rights activist, expressed her health and economic challenges during similar tumultuous times by saying, “I’m Sick and Tired of Being Sick and Tired,” which also conveys the current health and economic conditions faced by far too many Blacks trying to cope with COVID-19. Our findings of racial differences in the appraisal of personal implications of COVID-19 differ from previous studies on self-appraisal. Existing research has reported that Blacks consider stressors as less upsetting than Whites. The inconsistency in findings could be due to differences in the type of stressors that people have been asked to appraise. Previous studies tend to ask people to appraise individual-level events (e.g., life events) (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Turner & Wheaton, 1995; Cohen et al. 2019; Park & George, 2013) than a global event that our study does. Self-appraisal is likely to be racially mediated (Williams et al., 1997). The stressfulness of a life experience is determined, in part, by the meaning it has for the individual. The appraisal of an event is linked to an individual’s personal and social history, which differ across racial groups. Blacks appraise an individual-level stressor against the backdrop of adverse life events that they have experienced over the life course, but the same dynamic may not apply to a global pandemic.

Our findings underscore the need to consider the unique role of racialized coping resources in shaping disparities in later life psychological well-being. Despite their concerns, Black adults report fewer depressive symptoms and lower anxiety than White adults. Our findings indicate that better psychological well-being among Black adults could be due to coping resources such as emotional support, subjective religiosity, and religious coping. These coping resources may help them counteract the concerns they have about the pandemic. Similar to existing studies, we find that individuals with positive emotions, such as receiving greater emotional support, have fewer depressive symptoms and lower anxiety (Kahana et al., 2021).

Our study finds subjective religiosity and religious coping to be among the most salient ways for Blacks to cope with structural disadvantages. The positive effects of religious coping on the psychological well-being of Black older adults reinforce an underlying assumption of the social role of the “Black Church” on psychological well-being. The Black church and religion have played a prominent role in Blacks’ lives (Blank et al., 2002; Barnes, 2013). The Black church has offered a space to form a faith-based community, the relevance of which continues beyond the church. Faith has been at the heart of the Black community’s struggle for survival and is recounted in historical and contemporary writings (Romero, 2005). Faith-based perspectives, such as biblical admonitions of “man shall not live by bread alone; and “The word of God is, health to the bone and marrow of those who find it,” are important values, attitudes, and beliefs for Blacks that helps us to understand why Blacks in our study despite existing health disadvantages and worsening economic conditions due to the pandemic are concerned but report lower depressive symptoms and less anxiety than whites.

Resilience and Denial

Despite considering the influence of religious coping, subjective religiosity, and emotional support, Blacks continue to report significantly fewer depressive symptoms and anxiety. Resilience and denial may explain why Black older adults are less anxious and depressed than whites during a pandemic. For over 400 years since the first documented arrival of Africans who came to America by way of Point Comfort, Va. in August 1619, they have been exposed to unimaginable brutality of slavery, ensuing historical eras such as Reconstruction and Jim Crow, and continuing racial oppression (Wyatt-Nichol & Seabrook, 2016). These experiences have all reinforced among Blacks an emphasis on overcoming obstacles against all odds (Becker & Newson, 2005). Such emphasis contributed to the adaptation of a resilience philosophy rooted in their long struggle for freedom and equality. Breznitz (1983) has suggested that stress and denial go hand in hand; in extreme forms, denial can be pathological. Lazarus and Folkman (1984) suggest denial-like processes used as coping mechanisms might adversely affect psychological health status. For example, the perilous effects of racism could lead to maladaptive coping, such as engaging in alcohol and drug abuse, violence, self-blame, suicide, and remaining in denial.

According to Breznitz, sometimes denial can save us from breaking under strain. Some degree of denial may help to maintain a belief in a “just world” and the fairness of others, avoid feelings of powerlessness and vulnerability and conserve emotional energy, blocking out the negativity of any kind (Crosby, 1984; Harrell, 2000). Those who deny their distress have been found to report higher degrees of happiness and life satisfaction (Johnson & Crowley, 1996). The denial of stress among Blacks may reflect their socialization in the tradition of an African-American folk hero named “John Henry.” Having a “John Henry” personality is symbolic of some Black people who try to overcome all odds, no matter what the obstacles, even though denying the existence of real problems that may be insurmountable can lead to detrimental health outcomes (Lincoln et al., 2003). We speculate that even though Blacks are concerned about the COVID-19, they deny negative thoughts or emotions about the impact COVID-19 could have on them, leading to lower depressive symptoms and anxiety than whites.

Policy Implications

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed huge health inequalities in the U.S. The disproportionate COVID-19 related deaths among racial and ethnic minorities reflect the unequal burden of pre-existing health conditions. Greater concerns about COVID-19 among Blacks relative to their White counterparts is likely driven by their material disadvantages in terms of income, wealth, and health. Our findings point to the urgent need for policies that will mitigate concerns of racial and ethnic minorities, especially those experiencing financial hardship in the US. They indicate a need for macro-level policies that attempt to reduce the disproportionate burden of COVID-19 among racial and ethnic groups with a greater risk of infection, hospitalization, and death. The policies should be designed to address both the immediate crisis and the possible long-term implications. State and local legislators should forge a partnership with local clinics, hospital systems, faith-based institutions, and community organizations to help those grieving the loss of loved ones to COVID-19. Care should be given to creating institutional mechanisms that can offer culturally sensitive support services and interventions to help them cope with the various stressors (e.g., job loss, death of a family member) caused by pandemic. In addition to the disturbing loss of lives among Blacks, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused massive economic pain. Congress should continue to provide cash benefits and unemployment reliefs. This will provide them additional coping resources to lessen their concerns, thereby reducing their adverse impacts on psychological well-being outcomes.

Our study documented that Blacks are more likely to utilize religious coping when dealing with a stressful situation. At an individual level, the reliance on religious coping could help them adapt to the adverse circumstances created by the COVID-19 pandemic. Such reliance may not, however, alleviate the stress of job loss or a stressful work environment. They may say they are “too blessed to be stressed,” but underlying that statement may hide the suffering they are going through because of economic conditions or other structural problems. We call this phenomenon “suppressed inequality” because such cognitive denial is likely to mask mental health disparities. The denial, emanating from continued exposure to the oppression of opportunity, resources, power, results in minimizing any negative emotional experiences. An individual from oppressed and exploited groups could become so used to hiding stress caused by adverse material circumstances that they don’t even recognize their own feelings because they have dismissed them for so long. Such denial could lead to the minimization of potential mental health issues, and that, coupled with the lack of health care coverage, could discourage them from seeking help from mental health professionals. Excessive reliance on religious coping could contribute to the positive evaluation of psychological health, which then runs the risk of suppressing racial inequalities in mental health. Without demanding structural solutions to alleviate pain and suffering due to stressful material conditions, the situation of potentially suppressed racial disparities in mental health is likely to remain unchanged.

Limitations

Despite significant scholarly and policy implications, we are cognizant of the limitations of our study. Black participants in the study are underrepresented in proportion to the population of Black Americans in the U.S. (7% in the sample vs. 13% of the U.S. population). Given the nature of our data collection (i.e., the non-probability sample obtained from web-based survey), the likelihood of self-selection bias is unavoidable. Our sample has a higher percentage of women and very low participation of individuals with no education and less than high school education. We recognize that disproportionate representation of women and higher educated individuals is likely to bias our findings and make it less likely to be generalizable to the larger population of the United States. Our measure of emotional support could be improved by future studies. The measure of emotional support used in our study combines support from family, friends, and neighbors, making it difficult to distinguish the sources of social support, and their potentially differential impacts on psychological well-being.

Acknowledgement: This work was supported by funding from the Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing Zeta Kappa-At-Large Chapter.

References

Ano, G. G., & Vasconcelles, E. B. (2005). Religious coping and psychological adjustment to stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(4), 461-480. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20049.

Assari, S., & Lankarani, M. M. (2018). Secular and religious social support better protect blacks than whites against depressive symptoms. Behavioral Sciences, 8(5), 46. doi: 10.3390/bs8050046

Ayalon, L., & Gum, A. M. (2011). The relationships between major lifetime discrimination, everyday discrimination, and mental health in three racial and ethnic groups of older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 15(5), 587-594. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.543664

Barber, S. J., & Kim, H. (2021). COVID-19 worries and behavior changes in older and younger men and women. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(2), e17–e23. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa068

Becker, G. & Newsom, E (2005). Resilience in the face of serious illness among chronically ill blacks in later life. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60(4), S214–S223. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.4.s214.

Berry, M. F. & Blassingame, J. W. (1982). Long memory: The Black experience in America. Oxford University Press.

Besheer M., Cox, K., Diamant, J., & Gecewicz, C. (2021). Faith among Black Americans. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewforum.org/2021/02/16/faith-among-black-americans/

Blank, M. B., Mahmood, M., Fox, J. C., & Guterbock, T. (2002). Alternative mental health services: The role of the Black church in the South. American Journal of Public Health, 92(10), 1668-1672. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.10.1668

Breznitz, S. (1983). The denial of stress. Intl Universities Pr Inc.

Brown, L., Mitchell, U. A, & Ailshire J. A. (2018). Disentangling the stress process: Race/ethnic differences in the exposure and appraisal of chronic stressors among older adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences,

Brondolo, E., Gallo, L. C., & Myers, H. F. (2009). Race, racism and health: Disparities, mechanisms, and interventions. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32(1), 1. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9190-3.

Chatters, L. M., Taylor, H. O., Nicklett, E. J., & Taylor, R. J. (2018). Correlates of objective social isolation from family and friends among older adults. Healthcare, 6(1), 24. doi: 10.3390/healthcare6010024

Chatters, L. M., Taylor, H. O., & Taylor, R. J. (2020). Older Black Americans during COVID-19: Race and age double jeopardy. Health Education and Behavior, 47(6), 855–860. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198120965513

Clark, R., Anderson, N. B., Clark, V. R., & Williams, D. R. (1999). Racism as a stressor for Blacks: A biopsychosocial model. The American Psychologist, 54(10), 805–816.

Cobb, R. J., Erving, C. L., & Carson Byrd, W. (2021). Perceived COVID-19 health threat

increases psychological distress among Black Americans. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 44(5), 806-818.

Cohen, S., Murphy, M. L. M., & Prather, A. A. (2019). Ten surprising facts about stressful life events and disease risk. Annual Review of Psychology, 70, 577-597. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102857

Crosby, F. (1984). The denial of personal discrimination. American Behavioral Scientist, 27,

371-386.

Davenport, A. D., & McClintock, H. F. (2021). Religiosity and attitudes toward treatment for

mental health in the Black church. Race and Social Problems, 1-8.

Ellison, C. G. (2017). Religious involvement and subjective well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 32(1), 80-99.

Gallo, J. J., Cooper-Patrick, L., & Lesikar, S. (1998). Depressive symptoms of Whites and African Americans aged 60 years and older. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 53B(5), P277-P286. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/53B.5.P277

Gauthier, G. R., Smith, J. A., García, C., Garcia, M. A., & Thomas, P. A. (2020). Exacerbating

inequalities: Social networks, racial/ethnic disparities, and the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(3), 88–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa117

Garcia, M. A., Homan, P. A., García, C., & Brown, T. H. (2020). The color of COVID-19:

Structural racism and the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on older Black and Latinx adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(3), 75–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa114

Harrell, S.P. (2000). A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: Implications

for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70(1), 42-57.

Johnson, R. & Crowley, J. (1996). An analysis of stress denial. In H. W. Neighbors & J. S. Jackson (Eds.), Mental health in Black America (pp. 62-76). Sage Publications, Inc.

Kahana, E., Bhatta, T. R., Kahana, B., & Lekhak, N. (2021). Loving others: The impact of compassionate love on later life psychological well-being. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(2), 391-402. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa188

Kahana, E., Kahana, B., & Lee, J. E. (2014). Proactive approaches to successful aging: One clear path through the forest. Gerontology, 60(5), 466-474. doi: 10.1159/000360222

Kawachi, I., Daniels, N., Robinson, D. E. (2005). Health disparities by race and class: Why both matter. Health Affairs, 24(2), 343-352. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.343

Krause, N. (2005). God-mediated control and psychological well-being in late life. Research on Aging, 27(2), 136-164. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027504270475

Krause, N., & Chatters, L. M. (2005). Exploring race differences in a multidimensional battery of prayer measures among older adults. Sociology of Religion, 66(1), 23-43. https://doi.org/10.2307/4153114

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company.

Lincoln, K. D., Chatters, L. M., & Taylor, R. J. (2003). Psychological distress among Black and White Americans: Differential effects of social support, negative interaction and personal control. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44(3), 390.

Lukachko, A., Myer, I., & Hankerson, S. (2015). Religiosity and mental health service utilization among African Americans. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 203(8), 578.

Mezuk, B., Abdou, C. M., Hudson, D., Kershaw, K. N., Rafferty, J. A., Lee, H., & Jackson, J. S. (2013). “White box” epidemiology and the social neuroscience of health behaviors: The environmental affordances model. Society and Mental Health, 3.

Mouzon, D. M., Taylor, R. J., Nguyen, A. W., & Chatters, L. M. (2016). Serious psychological

distress among Blacks: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. Journal of Community Psychology, 44, 765–780. doi:10.1002/ jcop.21800

National Center for Health Statistics. (2021). Deaths involving coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) by race and Hispanic origin group and age, by state. https://data.cdc.gov/NCHS/Deaths-involving-coronavirus-disease-2019-COVID-19/ks3g-spdg

Nguyen, A. W., Chatters, L. M., Taylor, R. J., Aranda, M. P., Lincoln, K. D., & Thomas, C. S. (2018). Discrimination, serious psychological distress, and church-based emotional support among African American men across the life span. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 73(2), 198-207.

Nguyen, A. W. (2020). Religion and mental health in racial and ethnic minority populations: A review of the literature. Innovation in Aging, 4(5), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igaa035

Oppel, R., Gebeloff, R., Lai, R., Wright, W., & Smith, M. (2020, July 5) The fullest look yet at the racial inequity of Coronavirus. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/05/us/coronavirus-latinos-african-americans-cdc-data.html

Park, C. L., & George, L. S. (2013). Assessing meaning and meaning making in the context of stressful life events: Measurement tools and approaches. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 8(6), 483-5.

Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2000). Influences of socioeconomic status, social network, and competence on subjective well-being in later life: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 15(2), 187-224.

Robinson-Dooley, V., & Wade-Berg, J. (2015). Invisible voices: Factors associated with the subjective well-being of aging African American men. Educational Gerontology, 41(3), 167-181.

Romero, C. (2005). Creating the beloved community: Religion, race, and nation in Toni Morrison’s “paradise.” African American Review, 39(3), 415-430.

Smith, E. A. & Zerubavel, E. (2010). Bridging identities through identity change. Social Psychology Quarterly, 73(4): 320-321.

Stephanson, A., & West, C. (1989). Interview with Cornel West. Social Text (21), 269-286. doi:10.2307/827819

The COVID Tracking Project. (2021). COVID-19 is affecting Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and other people of color the most. The Atlantic Monthly Group. https://covidtracking.com/race

Taylor, R. J. (2020). Race and mental health among older adults: Within- and between-group comparisons. Innovation in Aging, 4(5), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igaa056

Taylor, R. J., Chatters, L. M., & Levin, J. (2004). Religion in the lives of African Americans: Social, psychological, and health perspectives. Sage Publications, Inc.

Taylor, R. J., & Chatters, L. M. (2020). Psychiatric disorders among older Black Americans: Within- and between-group differences. Innovation in Aging, 4(3), 1–16.

Turner, R. J., & Wheaton, B. (1995). Checklist measurement of stressful life events. In S. Cohen, R. C., Kessler, & L. U. Gordon (Eds.), Measuring stress: A guide for health and social scientists (pp. 29-58). Oxford University Press.

Villani, D., Sorgente, A., Iannello, P., & Antonietti, A. (2019). The role of spirituality and religiosity in subjective well-being of individuals with different religious status. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1525.

Ward, A. M. (2010). The relationship between religiosity and religious coping to stress reactivity and psychological well-being. Dissertation, Georgia State University. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/cps_diss/50

Williams, D. R. (1997). Racial differences in physical and mental health. Journal of Health Psychology, 2(3), 335–351.

Williams, D. R., Neighbors, H. W., Jackson, J. S. (2008). Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health, 98(Suppl 1), S29-S37. doi: 10.2105/ajph.98.supplement_1.s29

Wyatt-Nichol, H., & Seabrook, R. (2016). The ugly side of America: Institutional oppression and race. Journal of Public Management and Social Policy, 23(1), 20-46.

Ano, G. G., & Vasconcelles, E. B. (2005). Religious coping and psychological adjustment to stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(4), 461-480. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20049.

Assari, S., & Lankarani, M. M. (2018). Secular and religious social support better protect blacks than whites against depressive symptoms. Behavioral Sciences, 8(5), 46. doi: 10.3390/bs8050046

Ayalon, L., & Gum, A. M. (2011). The relationships between major lifetime discrimination, everyday discrimination, and mental health in three racial and ethnic groups of older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 15(5), 587-594. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.543664

Barber, S. J., & Kim, H. (2021). COVID-19 worries and behavior changes in older and younger men and women. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(2), e17–e23. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa068

Becker, G. & Newsom, E (2005). Resilience in the face of serious illness among chronically ill blacks in later life. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60(4), S214–S223. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.4.s214.

Berry, M. F. & Blassingame, J. W. (1982). Long memory: The Black experience in America. Oxford University Press.

Besheer M., Cox, K., Diamant, J., & Gecewicz, C. (2021). Faith among Black Americans. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewforum.org/2021/02/16/faith-among-black-americans/

Blank, M. B., Mahmood, M., Fox, J. C., & Guterbock, T. (2002). Alternative mental health services: The role of the Black church in the South. American Journal of Public Health, 92(10), 1668-1672. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.10.1668

Breznitz, S. (1983). The denial of stress. Intl Universities Pr Inc.

Brown, L., Mitchell, U. A, & Ailshire J. A. (2018). Disentangling the stress process: Race/ethnic differences in the exposure and appraisal of chronic stressors among older adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences,

Brondolo, E., Gallo, L. C., & Myers, H. F. (2009). Race, racism and health: Disparities, mechanisms, and interventions. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32(1), 1. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9190-3.

Chatters, L. M., Taylor, H. O., Nicklett, E. J., & Taylor, R. J. (2018). Correlates of objective social isolation from family and friends among older adults. Healthcare, 6(1), 24. doi: 10.3390/healthcare6010024

Chatters, L. M., Taylor, H. O., & Taylor, R. J. (2020). Older Black Americans during COVID-19: Race and age double jeopardy. Health Education and Behavior, 47(6), 855–860. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198120965513

Clark, R., Anderson, N. B., Clark, V. R., & Williams, D. R. (1999). Racism as a stressor for Blacks: A biopsychosocial model. The American Psychologist, 54(10), 805–816.

Cobb, R. J., Erving, C. L., & Carson Byrd, W. (2021). Perceived COVID-19 health threat

increases psychological distress among Black Americans. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 44(5), 806-818.

Cohen, S., Murphy, M. L. M., & Prather, A. A. (2019). Ten surprising facts about stressful life events and disease risk. Annual Review of Psychology, 70, 577-597. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102857

Crosby, F. (1984). The denial of personal discrimination. American Behavioral Scientist, 27,

371-386.

Davenport, A. D., & McClintock, H. F. (2021). Religiosity and attitudes toward treatment for

mental health in the Black church. Race and Social Problems, 1-8.

Ellison, C. G. (2017). Religious involvement and subjective well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 32(1), 80-99.

Gallo, J. J., Cooper-Patrick, L., & Lesikar, S. (1998). Depressive symptoms of Whites and African Americans aged 60 years and older. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 53B(5), P277-P286. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/53B.5.P277

Gauthier, G. R., Smith, J. A., García, C., Garcia, M. A., & Thomas, P. A. (2020). Exacerbating

inequalities: Social networks, racial/ethnic disparities, and the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(3), 88–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa117

Garcia, M. A., Homan, P. A., García, C., & Brown, T. H. (2020). The color of COVID-19:

Structural racism and the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on older Black and Latinx adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(3), 75–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa114

Harrell, S.P. (2000). A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: Implications

for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70(1), 42-57.

Johnson, R. & Crowley, J. (1996). An analysis of stress denial. In H. W. Neighbors & J. S. Jackson (Eds.), Mental health in Black America (pp. 62-76). Sage Publications, Inc.

Kahana, E., Bhatta, T. R., Kahana, B., & Lekhak, N. (2021). Loving others: The impact of compassionate love on later life psychological well-being. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(2), 391-402. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa188

Kahana, E., Kahana, B., & Lee, J. E. (2014). Proactive approaches to successful aging: One clear path through the forest. Gerontology, 60(5), 466-474. doi: 10.1159/000360222

Kawachi, I., Daniels, N., Robinson, D. E. (2005). Health disparities by race and class: Why both matter. Health Affairs, 24(2), 343-352. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.343

Krause, N. (2005). God-mediated control and psychological well-being in late life. Research on Aging, 27(2), 136-164. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027504270475

Krause, N., & Chatters, L. M. (2005). Exploring race differences in a multidimensional battery of prayer measures among older adults. Sociology of Religion, 66(1), 23-43. https://doi.org/10.2307/4153114

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company.